The Rio Grande is no longer a reliable source of water for South Texas.

That’s the sobering conclusion Rio Grande Valley officials are facing as water levels at the international reservoirs that feed into the river remain dangerously low — and a hurricane that could have quenched the area’s thirst turned away from the region as it neared the Texas coast.

Although a high number of storms are forecast this hurricane season, relief is far from guaranteed as the drought drags on.

For now, the state’s most southern cities have enough drinking water for residents. However, the region’s agricultural roots created a system that could jeopardize that supply. Cities here are set up to depend on irrigation districts, which supply untreated waters to farmers, to deliver water that will eventually go to residents. This setup has meant that as river water for farmers has been cut off, the supply of municipal water faces an uncertain future.

This risk has prompted a growing interest among water districts, water corporations, and public utilities that supply water to residents across the Valley to look elsewhere for their water needs. But for several small, rural communities that make up a large portion of the Valley, investing millions into upgrading their water treatment methods may still be out of reach.

A new water treatment facility for Edinburg will undoubtedly cost millions of dollars, but Tom Reyna, assistant city manager, believes the high initial investment will be worth it in the long run.

“We see the future and we’ve got to find different water alternatives, sources,” Reyna said. “You know how they used to say water is gold? Now it’s platinum.”

For Edinburg, one of the fastest growing cities in the Valley, the need for water will only grow as its population does. While the city hasn’t faced a water supply issue yet, the ongoing water shortage in South Texas combined with the growing population has put local officials on alert for the future of their water supply.

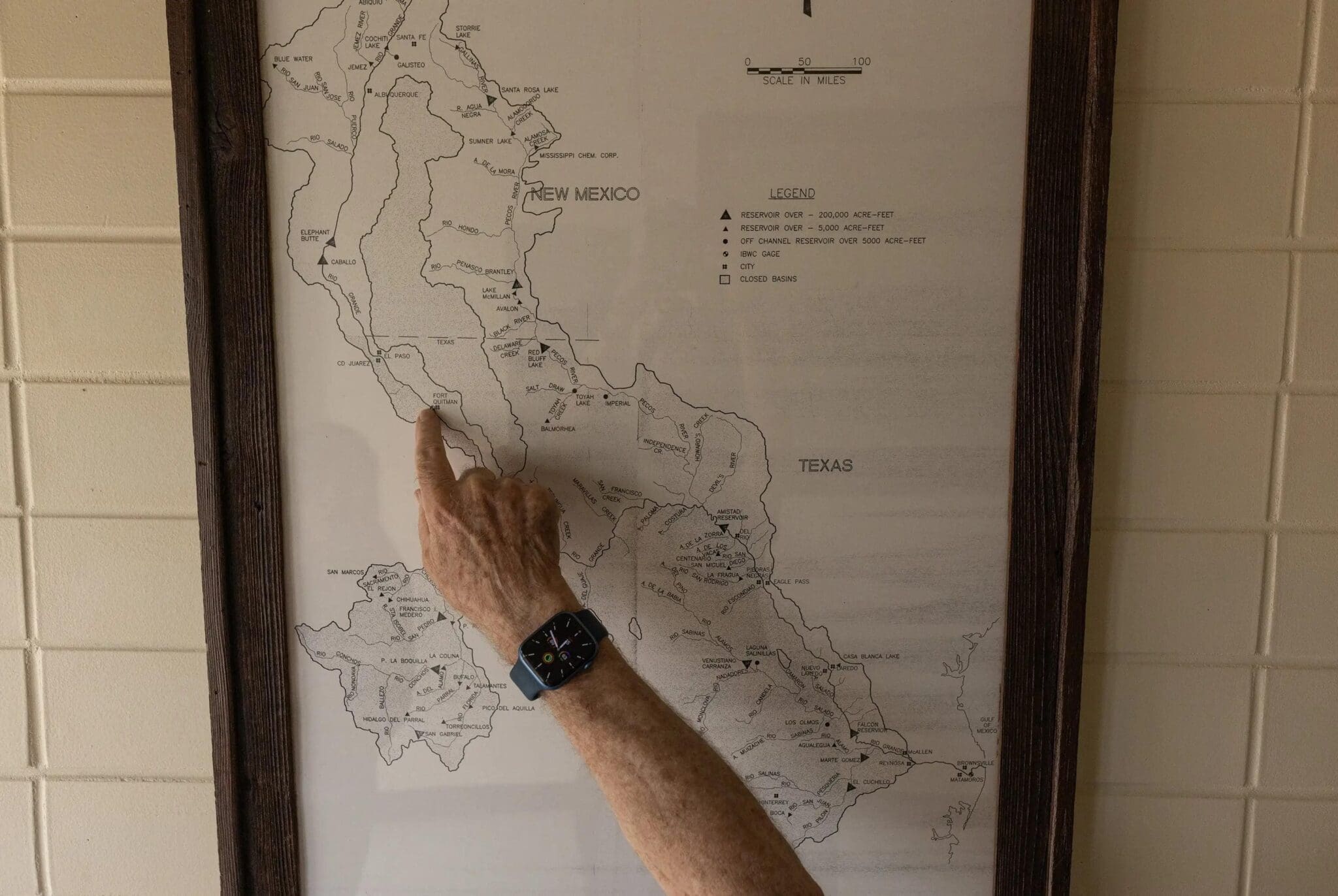

The Falcon and Amistad International reservoirs feed water directly into the Rio Grande. And while water levels have been low, cities and public utilities have instituted water restrictions that limit when residents can use sprinkler systems and prohibit the washing of paved areas.

Cities have priority over agriculture when it comes to water in the reservoirs. Currently, the reservoirs have about 750,000 acre feet, of which 225,000 acre feet are reserved for cities.

Of those 225,000 acre feet, each city or public utility or water supply corporation can purchase what are known as “water rights” which grant permission from the state to use that water.

But without water for farming, more and more of the water that cities own is being lost just in transporting the water to their facilities, and that’s directly due to the loss of water for farmers.

This relationship with the agriculture industry arose because irrigation districts were created here first. Cities came after, and because they used less water, they were set up to depend on irrigation districts.

Water meant for residential use rides atop irrigation water to water treatment plants. Without irrigation water, cities start to use water they already own to push the rest of their water from the river to a water treatment facility. It’s referred to as “push water.” Much of that water is lost for this purpose.

When water levels at the reservoirs got dangerously low in in the late 1990s, the average city would only get about 68 percent of the water it owned because the rest would be used as push water, according to Jim Darling, board member of the Rio Grande Regional Water Authority and chair of the local water planning group, a subset of the Texas Water Development Board.

The board is tasked with managing the state’s water supply.

Darling, a former McAllen mayor, has been trying to get cities to think of ways to increase their water supply.

As cities try to temper water demand by issuing restrictions on water usage, Darling said public utilities need to think about the drought not just from the standpoint of managing demand but also by increasing supply.

Darling has been floating the idea of creating a water bank of push water so that water districts can get by without having to go through the process of obtaining approval from the state for more water.

These discussions have been ongoing with the watermaster from the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, who ensures compliance with water rights. The talks are still preliminary, but a conversation with the watermaster’s office in early July revealed that three or four of the Valley’s 27 irrigation districts were out of water.

“Something needs to be done,” Darling said.

Edinburg’s proposed water plant is still in the early planning stages, but the goal is to stave off water woes by turning to water sources underground.

The plan is to dig up water from the underground aquifers as well as reuse wastewater. The two sources of water would be blended and treated through reverse osmosis.

Reserve osmosis consists of pushing water through membranes, large cylinders that filter the water. This is done several times until the water is pure and meets drinking water standards set by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality.

This method isn’t new.

By implementing this practice, Edinburg is following in the footsteps of the North Alamo Water Supply Corporation, a utility that supplies water to eastern Hidalgo County, Willacy County, and northwestern Cameron County.

After the drought in 1998, North Alamo turned to reverse osmosis in the early 2000s.

Its facilities currently treat about 10 million gallons of water per day through reverse osmosis, which represents one-third of all the water it treats. The rest is surface water from the river, but the utility aims to switch that split, treating two-thirds through reverse osmosis and only a third of surface water.

“We’ve got that mindset that we have to get away from the river,” said Steven P. Sanchez, general manager of North Alamo. “We have to start going to reverse osmosis.”

Hidalgo County officials are trying to take a more “innovative” approach to the area’s water problems.

In April, county officials touted a proposed regional water supply project, dubbed the Delta Water Reclamation Project, that would capture and treat stormwater to be used as drinking water.

The project, expected to cost $60 to 70 million, started off as a project to mitigate flooding by drawing water away from a regional drainage system. But now, plans include a water plant that would take daily runoff and treat it through reverse osmosis.

“We are the first drainage district to do something like this and of course that’s an exciting thing for us, to be able to do something that’s so innovative and green,” said Hidalgo County Commissioner David Fuentes, who sits on the drainage district board. “But it comes with a lot of obstacles and a lot of unknowns.”

One challenge will be financing the water plant. Drainage districts are limited on the bonds they can issue in exchange for a loan. Obtaining funds from the Texas Water Development Board would also be an uphill battle since a drainage district doesn’t fit the usual metrics that a water supply corporation does.

County leaders made the case for their project before a Texas Senate committee hearing in May on water and agriculture, requesting that legislative leaders direct the water development board to give a higher consideration to projects like theirs or to provide a grant program their project would qualify for.

The county drainage district already completed a pilot test of the project and those results are now under TCEQ for review. Leaders expect TCEQ will give them the green light as well as instructions on how to design the plant and steps they need to take to ensure water quality.

Fuentes said they expect that review to be completed early in the legislative session, which would give them a better idea of what they need to ask legislators for.

If the project becomes a reality, the county would sell to water corporations like North Alamo.

In Cameron County, located on the east end of the Valley, the Brownsville Public Utilities Board was also motivated by drought conditions to reduce dependence on the river. With help from partners in the Southmost Regional Water Authority, the public utilities board spearheaded the construction of a desalination facility that also employs reverse osmosis.

Despite its growing popularity in the Valley, desalination has its drawbacks. The practice has faced pushback from environmentalists over the disposal of the concentrated salts and because the process requires a lot of energy.

Southmost and North Alamo hold permits from TCEQ to discharge the concentrate, or reject water, into the Brownsville Ship Channel and a drainage ditch that flows to the Laguna Madre, respectively.

Representatives for both entities said the salinity of the concentrate is less than the salinity of the bodies of water that are receiving that discharge.

“All the aquatic life that’s there, the plant life and everything that feeds off that water is not being harmed at all,” Sanchez said. “We monitor that.”

Sanchez said another solution would be drying beds, a process of evaporating the water into sludge, and injecting the water about 20,000 feet back into the ground.

North Alamo has also made improvements to its energy consumption. In May, the water corporation upgraded its 16-year-old water filtering equipment, reducing the amount of energy used to create the pressure to push the water through its filtration system.

Sanchez said reverse osmosis has also been more efficient for North Alamo.

The utility’s surface water treatment plant treats about 2.7 million gallons of water daily, while the reverse osmosis plant treats 3 million gallons. It’s also become cheaper in the last few years. Treatment of surface water costs $1.21 per thousand gallons while reverse osmosis costs $0.65 per thousand gallons, according to Sanchez, who said reverse osmosis would still be cheaper even with depreciation.

This wasn’t always the case, he said, but the high cost of chemicals has driven up the cost of treating surface water. But where surface water treatment is cheaper is in the initial cost to establish it.

Sanchez estimated that the initial capital investment for reverse osmosis treatment capable of treating a million gallons per day would conservatively cost about $6 to 7 million, while a surface treatment facility of the same capacity would cost $3 to 4 million.

Southmost’s plans to double its plant’s capacity would cost an estimated $213 million.

Reyna, the Edinburg assistant city manager, agreed that the initial investment would be the biggest cost for the city, but believes it will end up paying for itself.

Not all cities have that as a viable option, though. That initial cost can be an insurmountable hurdle for smaller, rural communities, leaving them unable to invest in solutions. The state could possibly alleviate some of that cost.

During the last legislative session, lawmakers established the Texas Water Fund with a $1 billion dollar investment that will go to a number of financial assistance programs at the Texas Water Development, including one that has never had funding before, called the Rural Water Assistance Fund.

This will be additional state funding to help rural communities with technical assistance on how to decide what kind of design and what kind of assistance is best for their community. This will help them navigate the process of applying for funding.

Plans for how the water development board will allocate funds to these new financial assistance programs will be released in late July.

Sarah Kirkle, the director of policy and legislative affairs at the Texas Water Conservation Association expects the state will provide interest rate reductions for loans that will be used on expensive projects.

However, the $1 billion allocated to the Texas Water Fund will not get very far.

“The needs for implementing this state water plan are something like $80 billion and those are outdated numbers that we’re looking to update in the new water planning cycle,” Kirkle said, adding that the plan doesn’t include the cost of wastewater or flood infrastructure.

She noted that the cost of water infrastructure is about two or three times what it was before the COVID-19 pandemic because of disruptions in the supply chain and additional federal requirements for federally-funded projects.

Many small communities also don’t have the resources to plan for their needs, Kirkle said, so many of them don’t participate in the water planning process, leaving no one to speak up for them.

“We really need to make sure that as we see additional water scarcity around the state, that our communities are engaged in planning for their needs and understand where they might have risks and where their water might not be reliable,” Kirkle said.

Reporting in the Rio Grande Valley is supported in part by the Methodist Healthcare Ministries of South Texas Inc.

Excerpts or more from this article, originally published on Grist , was republished here, with permission, under a Creative Commons License.