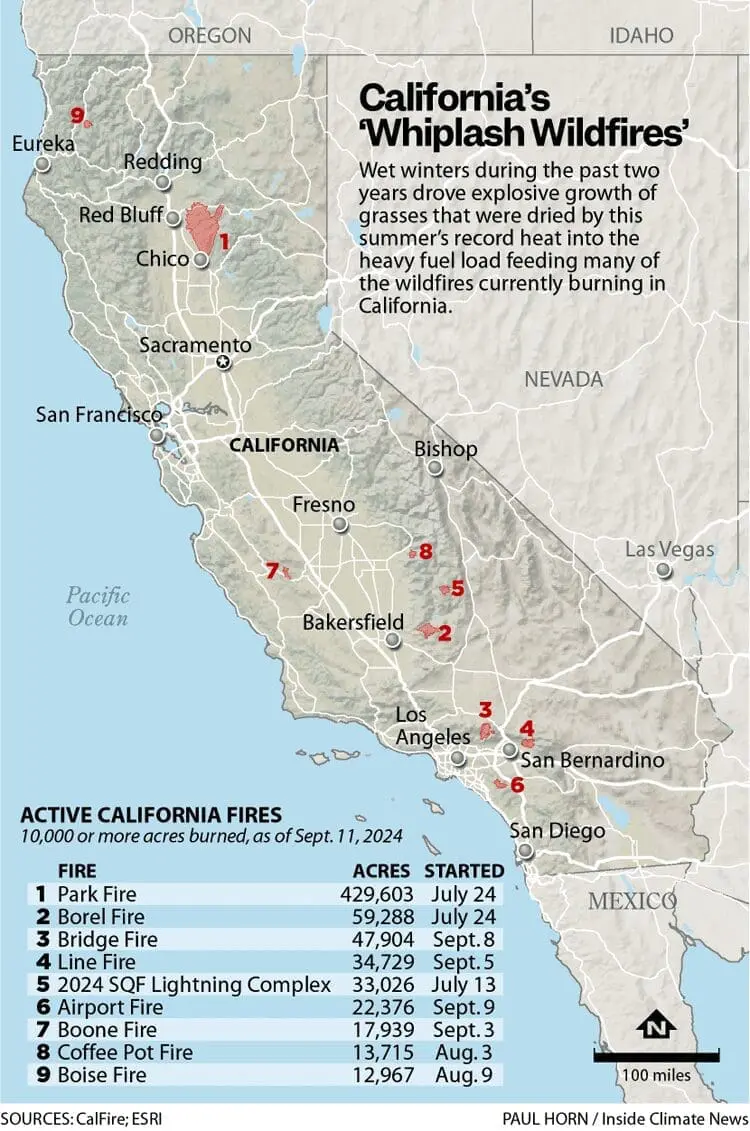

While many Californians are praying for rain heavy enough to slow the spread of the 6,078 fires that have burned 977,932 acres in the state this summer, firefighters and climatologists recognize that the heavy winter rains are a big part of what led this fire season to scorch around three times as much total acreage as in 2023.

After Northern California’s brutal summer of fire, including the massive Park Fire that is now the fourth largest wildfire in state history, Southern California exploded with fires this month. The Line Fire in San Bernardino County northeast of Los Angeles grew to 35,000 acres in the week since it ignited, threatening tens of thousands of homes and forcing the evacuation of thousands of residents.

While there were 5,053 fires that burned 253,755 acres by September 11 in 2023. By that date this year, about a thousand additional wildfires had collectively burned over 3.85 times more acres. Much of the increase can be attributed to what climatologists are calling “weather whiplash.”

Over the past four years, California’s weather has swung from drought between 2020 to 2022 to two excessively wet years in 2023 and early 2024. That moisture fueled a surge of growth of what are known as fine fuels — grasses, small shrubs, moss, and twigs that grow quickly and ignite easily.

Firefighters call them one-hour fuels because in just one hour, under dry, sunny conditions, they can dry to the point of catching fire.

Grassland ecosystems are more susceptible than trees to the weather whiplashes of recent years.

“A forest doesn’t appear or disappear or grow or die back just on the basis of one wet year versus another,” said Daniel Swain, a climate scientist at University of California, Los Angeles. “But if you have a grassland ecosystem, it can respond quite a bit to changes from year to year.”

While dry years leave a grassland looking like a dried out lawn, wet years can produce waist- or head-high grasses. When hot and dry conditions return, that heavy fuel load of grasses cures quickly, ignites easily, and burns hot and fast with flames that race across the landscape far faster than a forest fire to spread the blaze to trees or structures.

The previous two years’ wet winters and atmospheric rivers supercharged grass growth, but then the record-breaking summer heat cured vast grasslands into fuel.

“We added more fuel for the fire, and then we kiln-dried it, essentially, with that record-breaking heat,” said Swain.

The Park Fire, which has burned 429,603 acres of California this summer, is an excellent example of how grass can drive some of the West’s largest and most destructive wildfires. The fire ignited in remote grassland and shrubland and most of the acreage it has burned was in fine-fuel ecosystems. With a strong wind pushing them, the flames raced into denser vegetation and forests, where the heavier loads of biomass can feed far more energy into a fire. While many ground fires burn slow and low on forest floors, those with enough fuel can easily send flames up the branches of 100-foot-tall trees to ignite crown fires that race through forest canopies.

“It’s the worst of both worlds. We get the overly abundant grasses and we also get quite dry forests,” said Swain. “You can achieve that if you have a wet winter but then a record hot summer and fall to follow, which is what we’re seeing right now.”

Fast grass fires can also ignite wooden fence rails, decks, landscaping, and siding, to spread the fire through communities. Many homeowners who live in areas surrounded by grass do not realize their properties could be threatened by a wildfire the same way houses in forests are, but experts advise that they need to prepare their properties just as much as people whose homes are in the woods.

The danger comes from the speed of the fire. Grasslands ignite quickly — often near communities — and, when pushed by strong winds, the resulting fire will spread rapidly with the potential to use structures as new fuel.

In 2021, between Christmas and New Year’s Day, a rare wintertime grass fire exploded into the most destructive fire in Colorado history — in just two days. The Marshall Fire burned 1,084 homes and seven commercial buildings.

Around 80 percent of home loss from wildfires occurs in grasslands, said Ralph Bloemers, director of Fire Safe Communities for Green Oregon.

“Fire just is. Fire is inevitable,” said Bloemers. “The problem is the vulnerability of the communities that we’ve built in the fire plain, not the fire, because we aren’t going to eliminate the fire from a Western fire-prone, fire-adapted landscape. It is a natural reality.”

A study Bloemers co-authored emphasizes improving resilience in at-risk communities. Modifying structures and landscaping around communities can make them less likely to burn in a wildfire, and can reduce the potential for ignitions in conditions in which a fire could be difficult to control.

Woodland residents have long been advised to build with non-flammable roofs that are less likely to ignite, to remove bark mulch, shrubs, and wood piles away from their homes, and to reduce the density of flammable vegetation near their homes. While many residents whose homes are only surrounded by grassland and shrublands might believe their homes are at less risk, Bloemers says they need to be equally diligent in making their properties resilient to wildfires. Studies show that most home loss nationwide occurs in fast fires, and in grasslands and shrubland ecosystems. People need to be even more vigilant in avoiding starting a fire in easy-to-ignite dry grasses, for instance by avoiding using machinery that can create sparks in desiccated grasslands.

Aside from community preparation, the public must “be aware that people and human activity are responsible for the vast majority of vegetation fires — I’m talking north of 90 percent of [Cal Fire’s] fires are started by people and our activities,” said Isaac Sanchez, deputy chief of communications for Cal Fire.

A 2023 study found that wildfire-related structure loss was not just a function of acres burned. Instead, 76 percent of all structure loss in the West comes from unplanned human-related ignitions. Contrary to the historically-destructive Marshall Fire, which burned 6,080 acres, the Park Fire has destroyed 375 fewer structures while burning over 70 times as many acres. Thousands of personnel had achieved 99 percent containment of the blaze as of September 11.

As destructive fires powered by all fuel types are becoming more frequent, “we just simply cannot afford to be the careless fire people that we are early in the season and strain our suppression response,” said Bloemers.

More work is needed to reduce the loss associated with wildfire intensity and future years of “weather whiplash,” he said.

Excerpts or more from this article, originally published on Grist , was republished here, with permission, under a Creative Commons License.