This article was originally published by The Emancipator.

I grew up in Florida attending public high school during former President Donald Trump’s 2016 rise to power. My campus was majority-minority, and in many ways exemplified many stereotypes of the South: heavy police presence, no sex education, openly homophobic teachers, history assignments on whether the Civil War was about states’ rights.

To be teenaged, female, and brown in the early Trump “Make America Great Again” era — that is, to watch the breakdown of American democracy before you’d even had a chance to participate in it; to realize that the boys you dreaded in the school hallways and locker rooms would just graduate to bigger offices — was to constantly be on edge. It was only when I moved to California for college that I was struck by the gaping holes in my high school curriculum.

In four years of high school English classes, I was assigned only three works by women writers of color. Those books changed my life. In Maya Angelou’s “I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings,” in particular, I found a model for the life of a writer. Angelou was a Black woman writing in Jim Crow Arkansas. I was a brown girl in Florida, but the humanity and singularity of her voice still touched me, illustrating the boundless capacity of literature to uplift and transcend.

Literature for K-12 students has become a target in culture wars about race and American identity, whether it’s an uptick in book bans that disproportionately impact novels by LGBTQ+ writers and writers of color, attacks against antiracist pedagogy, or calls for the death of DEI. Often the backlash comes from conservatives, who claim baselessly that antiracist literature makes White children uncomfortable or promotes unnecessary division.

No book should ever be banned, but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t shake up stale curriculums. In a recent viral video, BookToker and educator Cody West offered his perspective on high school classics he considered “overdone or outdated,” with suggestions of what to teach instead.

It’s also true that so many high school English classics are musty at best, demoralizing and actively harmful at worst, doing a disservice to young people’s education and limiting their imaginations of what literature can be. I also blame high school curriculums for dampening people’s interest in reading and creating an epidemic of bad taste. (If a guy lists “The Great Gatsby” as a favorite book on his dating profile, that’s how you know he hasn’t read a full book since senior year.)

Here are my suggestions, as a Gen Z reader and writer, on five books to retire and five books to read instead:

Out: White saviors

“To Kill A Mockingbird” holds deep nostalgia for many American readers as a beautifully written narrative chronicling Scout, a young White girl in the Deep South, whose innocence is shattered by a lynching in her community. It’s often taught as a model of tolerance, exemplified by Scout’s father, Atticus, a White lawyer who defends a Black man wrongly accused of rape. “To Kill A Mockingbird” has faced bans since its publication in 1960 for its portrayals of racial violence, not to mention its use of 48 slurs.

It has also increasingly come under fire for a different reason: its white savior trope. Last year, teachers in Washington successfully challenged the book’s mandatory place on the freshman curriculum, claiming it “centers on Whiteness” at the expense of authentic Black perspectives, which alienates Black students. “You never really understand a person … until you climb inside of his skin and walk around in it,” Lee writes — which is why it might be time to set aside “Mockingbird” and walk with a different novel instead.

In: Women telling women’s stories

Literature of the South has never been more controversial. Last week, the New York Times published an article decrying the failures of DEI, citing a professor who complained, among other things, that “All Southern literature is now suspect.” (That professor had faced criticism for reading aloud the n-word in a Faulkner story.)

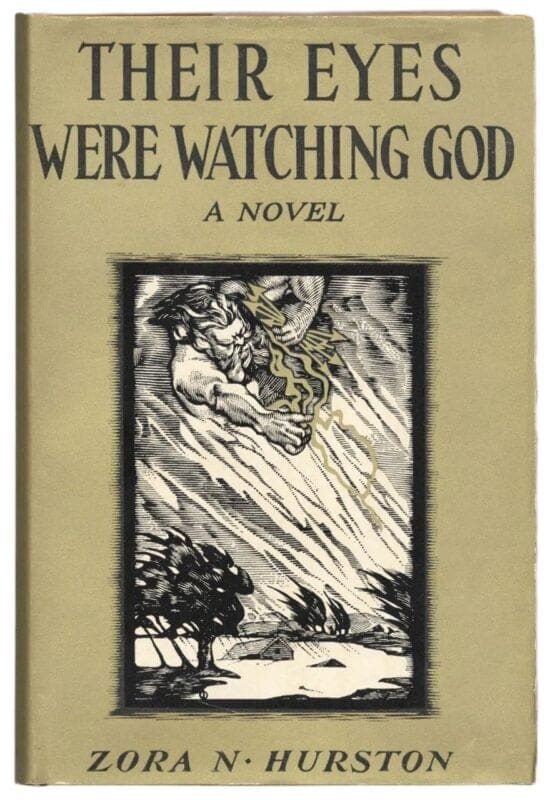

If we are going to defend literature from the South, it’s time to put some respect on “Their Eyes Were Watching God.” Zora Neale Hurston’s iconic 1937 novel also charts a coming-of-age arc, following Janie, a young Black woman in the South; like Scout, her innocence, too, is lost, as she is forced to shove aside revelations about her own potential and lead a small, cautious life as the granddaughter of a slavery survivor.

She yearns to “be a delegate to the big ‘ssociation of life.” As a spiritual predecessor to “doing it for the plot,” Janie’s quest leads her to fall in love three times as she journeys through the South. Hurston, an anthropologist by training, paints a nuanced and empathetic portrait of Black communities in Florida, exploring the legacy of slavery and issues like gender, color, and class. Hurston also writes partially in Black vernacular English, offering a different model of “historically accurate” language and place-specific prose.

Out: Voyages of ‘darkness’

“Heart of Darkness” was my biggest hate read in high school. Joseph Conrad’s 1899 novel about a European sailor’s journey through the Congo is frequently taught in English classes, I think, for two reasons: It’s short, which makes it accessible to students, and it’s heavy-handed in its metaphors (like, did you know the Heart of Darkness is actually Africa?).

While “Heart of Darkness” is ultimately a critique of European colonial barbarity, it makes its point by vacating the subjectivities of its African characters, reducing an entire continent into a dark landscape against which the White hero can confront his own inhumanity. I encountered the book again in college, this time in a course about British imperial literature, which was an illuminating context in which to dissect it. In high school, however, we read it unironically and without historical context. And when I pointed out the problematic tropes, I was the lone hater in the room. It turns out I had good company; the great Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe famously called the book “deplorable.” Enough said.

In: Voyages of strength

“Copper Sun” by Sharon M. Draper is a book I have not stopped thinking about since I read it at 13. Like “Heart of Darkness,” “Copper Sun” is a narrative of a voyage through unspeakable horrors, atmospheric and rooted in painful geographies, posing hard questions about the limits of our humanity. Published in 2006, “Copper Sun” follows two young women, Amari and Polly, an enslaved African girl and indentured White laborer respectively, navigating the Atlantic slave trade, plantation life, and their ultimate quest for freedom.

This book has a strong coming-of-age arc and teaches readers about the historical realities of the slave trade, experienced through Amari’s singular narration. What’s more, although novels about Black history are frequently banned because they make White children feel bad, Draper makes a powerful narrative choice to ground her novel in the complex friendship between Amari and Polly. The strength of their solidarity, despite frictions and racial power dynamics between the girls, makes “Copper Sun” a standout example of radical empathy.

Out: Kids as supervillains

“Lord of the Flies,” like much of public school itself, felt like a fever dream. This 1954 novel follows a group of pubescent British boys who get stranded on an island; some step up as leaders to find a way to survive, while others descend into savagery and violence. It’s popularly assigned, I think, for the same reasons as “Heart of Darkness”: It’s short and not particularly subtle in its allegory of civilization versus barbarism. Recognizing one’s own capacity for evil might have been revelatory to colonial era British readers, but I think there are much more interesting conversations to be had today, particularly when it comes to coping with these increasingly unprecedented times.

In: Kids as visionaries

“Parable of the Sower” also follows a teenage protagonist trying to lead her community to survival against all odds. In an apocalyptic United States where civil society has crumbled, a few lucky families live safely behind compound walls. The adults in charge of the compounds have grown complacent, so 14-year-old Lauren takes it upon herself to prepare for the end of the world. She develops an entire religious practice to prepare herself for the inevitability of change.

Her faith and vision in the face of deadly adult inadequacy feels resonant to a generation of teenagers who came of age during a deadly global pandemic and growing up with — and fighting back against — the specter of climate change and the general erosion of American democracy. Eerily enough, the dystopian future setting of “Parable of the Sower,” as Butler imagines it, begins in 2024. Sometimes, fiction mirrors reality.

Out: Boring musings on plants

The poetry of Robert Frost never impressed me, although I was made to nearly memorize it in my senior year of high school. Frost writes plainly, prosaically, of a quintessentially American landscape that includes snow, apples, birds, trees, lumberjacks, and somehow not a single person of color. Frost’s appeal, in my opinion, relies solely on nostalgia and deeply-held loyalty to what is “classic,” and therefore “good,” allowing him to take up valuable real estate in a poetic landscape that has benefited tremendously from newer, diverse voices.

In: Indigenous ecopoetics

“Postcolonial Love Poem” by Natalie Diaz shattered me and then reaffirmed my faith in the power of language to hold up a mirror to reality. Diaz is an Indigenous and Latinx poet whose work grapples with themes of environment and the American landscape, but her geographies are richly populated by her people, loved ones, and community. Diaz writes of her brother’s suffering with addiction, her experiences with racism and erasure, and her love for her land. “A good window lets the outside participate,” Diaz writes. “Postcolonial Love Poem” is a window and a gateway, and if there were any book to encourage budding writers, it is this one.

Out: Gaslighting teenage girls

I read “The Crucible” in the 10th grade, coincidentally during the height of the #MeToo movement in 2017. That year, girls like me watched carefully as women named their abuse at the hands of powerful men, resisted gaslighting and ridicule, and stood in their truth. Watching them, we took quiet notes on the women we would grow up to be. My conservative high school English teacher insisted that this 1953 dramatization of the Salem witch trials — an unsubtle allegory for McCarthyism — was actually about the untrustworthiness of girls, who liked to lie for attention.

While it’s likely few people who’ve read the play would agree with that take, there’s also the character of Tituba, an enslaved Black woman accused of witchcraft, who’s written as a caricature and blamed for inciting the whole affair — let’s give her a break. There are more interesting, contemporary works of literature about truth-telling, public discourse, and the politics of believability that are more likely to resonate with teenage girls.

In: Women speaking with their full chests

“Know My Name,” published in 2019 by Chanel Miller, deserves the status of a contemporary classic. It is not only a testament of a rape survivor’s resilience and dignity, but marks a shift in how we talk, think, and write about survivorhood. Miller offers hope to readers who have experienced something similar, and creates a model for more survivors to stake narrative space for themselves.

“Know My Name” is a masterclass in rhetoric, reimagining and remixing genres like the court testimony, the survivor narrative, and the personal memoir to persuade readers and push back against rape culture. It is also a narrative about narrative, specifically the way media and society regards survivors and perpetrators, and what it takes to regain one’s agency and voice. I genuinely believe that reading this in school could save a life.