Recently updated on August 6th, 2024 at 12:30 am

How officials are trying to prevent intimidation at drop boxes, hand-counting ballots, and other problems from the midterms.

Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. Sign up for our free newsletters here.

The governor and secretary of state are crafting proposals to clarify or change how Arizona’s elections are run, but it’s unclear if they will move forward prior to the presidential election, or would be enough to prevent a repeat of the controversies and errors from the midterm.

Voter intimidation at ballot drop boxes, efforts to hand-count ballots instead of using machines, and errors tabulating and counting ballots during the 2022 election raised questions about aspects of state election law that both voter advocates and Republican activists say deserve attention. Gov. Katie Hobbs and Secretary of State Adrian Fontes, both Democrats, have held months of meetings and solicited feedback in order to chart a way forward.

Their proposed solutions are largely emerging through two separate vehicles.

First, the Elections Procedures Manual, Fontes’ new version of the giant rulebook that dictates how elections in the state are run. Fontes submitted his final version of the new manual to Hobbs and Attorney General Kris Mayes earlier this month, and both must approve it by the end of the year in order for it to take effect. His first version drew pushback from across the political spectrum.

Second, through recommendations from a Bipartisan Elections Task Force that Hobbs created earlier this year. The task force is set to meet Tuesday to finalize its recommendations, and it is charged with giving Hobbs a final report by Nov. 1. But these are only recommendations, and it’s unclear if the Republican-controlled Legislature will be willing to change state law to adopt them. There’s a chance these laws could take effect for the presidential election, if they are enacted with emergency provisions or enacted quickly.

Republican state Sen. Ken Bennett said on Friday that he believes lawmakers might be willing to consider some of them. But he also said he doesn’t believe they go far enough to address much of the concern from election skeptics about security and fairness.

“I think they are going to be perceived as weak and nibbling around the edges,” he said.

Fontes told Votebeat Friday morning that his office has been working with the task force — composed of voting rights advocates and both Democratic and Republican former and current officials — to try to address issues where it can do so without having to change laws. And he is trying to use the manual to clarify portions of election law where that’s possible. But for some of 2022’s most high-profile controversies, such as errors in the ballot count in Pinal County, Fontes said the manual can’t help.

“You can’t regulate somebody away from making mistakes,” he said.

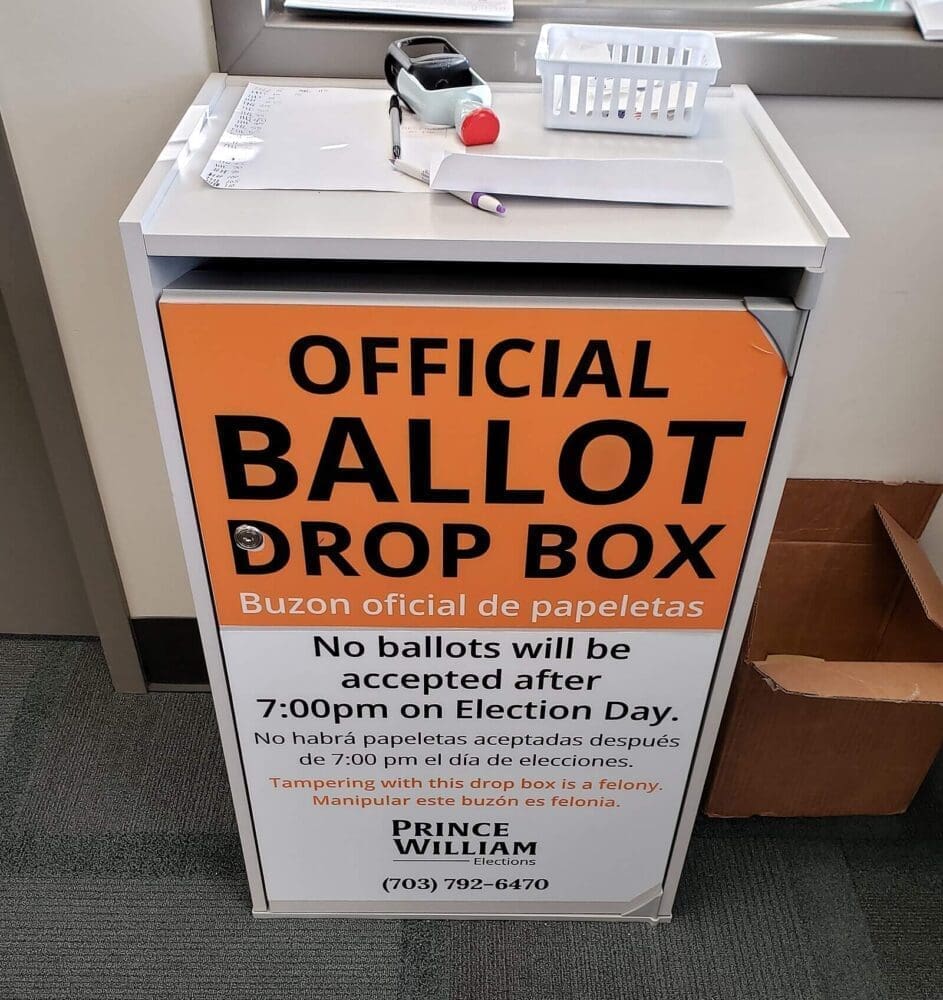

1. Casting ballots at drop boxes

Volunteers seeking proof of fraud watched over a few ballot drop boxes during the midterm election in Maricopa County, leading voters to file more than a dozen complaints of voter intimidation and leaving the election community with questions about whether the efforts were legal.

Fontes has now added language to his new manual to clarify that some of what ballot drop box watchers were doing should be considered voter intimidation, including following, photographing, or videotaping voters or poll workers.

But gray areas and questions remain. Does a rule for behavior within 75 feet of polling locations apply to ballot drop boxes? Are unstaffed ballot drop boxes even allowed under state law?

Voter advocates such as All Voting is Local want him to take it even farther and clarify that guns shouldn’t be allowed within 250 feet of a drop box, said Alex Gulotta, the organization’s Arizona director. This comes after drop box watchers were spotted near a drop box during the midterm election with guns and body armor.

But Republican House Speaker Ben Toma and Senate President Warren Petersen have told Fontes that he is overstepping his authority by dictating what constitutes voter intimidation, calling it an “extraordinary expropriation of legislative power.”

Hobbs’ task force wants language added to state law to address behavior that interferes with voters while they are dropping off their ballots, and will be voting on a recommendation Tuesday.

But there’s also a bigger challenge to the system looming. Arizona Free Enterprise Club and Thomas More Society filed a lawsuit last week in Yavapai County saying that Fontes can’t allow for unstaffed drop boxes, under state law. The organization writes that state law limits the use of drop boxes to locations that are monitored by election workers, which can include existing polling locations and the county elections office.

Fontes said in an interview Friday that the law does allow for unstaffed drop boxes. A spokesperson for his office later pointed to a law giving the secretary authority to use the manual to prescribe rules for how counties collect ballots.

The resolution of that lawsuit, along with any new version of the EPM, may offer voters clarity before the presidential election.

2. Hand-counting ballots

The Arizona Court of Appeals ruled this week that Cochise County supervisors were incorrect in believing the county could hand-count all ballots as part of its statutorily required post-election audit for the midterm election, instead of just auditing a portion of ballots cast.

The three-judge panel found that state law requires counties to start that audit with ballots cast on Election Day from at least 2% of the county’s precincts, or two precincts, whichever is greater, along with a set number of early ballots. Most telling, the judges found that a line in the current Elections Procedures Manual allowing counties to choose any number of early ballots for their initial hand-count audit was in conflict with state law, meaning it’s void and unenforceable.

“Because the legislature provided for a detailed method to verify the results from electronically tabulated voting machines, counties must follow that method unless and until the legislature determines otherwise,” the judges wrote.

Fontes has already removed that line about early ballots from his new version of the manual.

By issuing their opinion, the appeals court judges “did us a huge favor,” said Gulotta of All Voting is Local, by clarifying the rules for the audit before the next election.

But the case didn’t address whether counties legally must use machines to tabulate ballots on the initial count – something that Republican leaders have called into question in recent months.

To try to clear this up, Fontes added a line in the manual saying that, except when prescribed by a court or provided in law, no election that includes a federal, state, or county office, or ballot measure “shall be subject to a full hand count or a manual tabulation of ballots.” While that line was added to the section of the manual pertaining to the post-election audit, Fontes said it applies to the initial counting of votes as well.

He said that the manual or an addendum to the manual might be updated with more language on this topic, including the appeals court opinion.

It’s unclear if this law will see future challenges. Republican lawmakers have toured the state this year trying to convince county supervisors to ditch tabulation machines for the presidential election, but so far no county has been willing to go there. And with the March 19 presidential preference election quickly approaching, it’s becoming less likely for counties to change their plans now.

3. Trouble with ballot printers

The internal and independent reviews of Maricopa County’s Election Day problems found that better testing might have helped to identify the problem with the county’s ballot-on-demand printers prior to the election.

The county has replaced the faulty OKI printers with more robust printers better able to handle the long, thick ballot paper the county uses, so far spending $7.2 million on 645 new Lexmark printers and accompanying supplies, according to an Elections Department spokesperson.

While elections experts have said a more formal certification program or more testing requirements for on-demand ballot printers, used in most counties, might be warranted in Arizona, Fontes did not use the manual to require that.

In feedback on Fontes’ initial draft, the Arizona Republican Party called on Fontes to specify that counties must test ballot-on-demand printer functionality during the required pre-election test of voting equipment called the logic and accuracy test, “including by simulating real world printing conditions.” The Republican Party also said the manual should require election officers to “secure a print vendor’s written authorization to utilize the printer as a ballot-on-demand printer during county elections.”

Asked why he didn’t use the manual to change procedures in response to the printer problems, Fontes said that he believes Maricopa County is already on top of the issue.

Hobbs’ task force is planning to recommend a law ensuring that “tabulation-adjacent equipment” meets certain standards. But Fontes said that this is mainly related to security requirements, not functionality requirements.

4. Mistakes counting ballots

Pinal County’s election procedures fell apart during the 2022 midterm, and its recount found that it had initially failed to tabulate hundreds of ballots.

County officials have since been working on creating better processes, forms, and post-election auditing practices that will prevent future mistakes, and Pinal is in the process of hiring a new elections director.

Election advocates and experts told Votebeat that the state should consider stronger laws spelling out how election officials must double-check election results, consider improvements to the state’s hand-count audit, and provide better support and best practices to counties.

Hobbs’ task force is recommending that the Secretary of State’s Office establish best practices and training for ballot reconciliation and post-election audits.

Fontes said that his office already advises counties on best practices for ensuring accurate elections, including in ongoing training. But mistakes are going to happen, he said, and you can only do so much to prevent them.

“That’s why they are called mistakes,” he said.

Jen Fifield is a reporter for Votebeat based in Arizona. Contact Jen at jfifield@votebeat.org.

This article was originally published by Votebeat, a nonprofit news organization covering local election administration and voting access.