Last updated on August 6th, 2024 at 12:57 am

On this last day of a dying year, I can offer no words of wisdom about what the future will bring. Reflecting on our shared national experience that was 2023 affords me no insight into who we are as Americans or where we’re headed as a nation, unless division and uncertainty are directions. The headlines from publications big and small are a mosaic that is still too near our eyes to discern pattern or image.

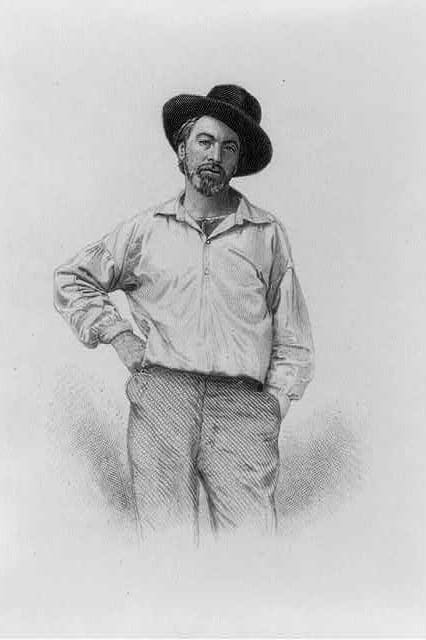

For days now, I’ve been pondering exactly how to describe the feeling that has overshadowed me and for days have come up with nothing. I made notes and outlines but could find no meaning. The closest I came was when I was reminded of Walt Whitman’s poem, “Year That Trembled and Reel’d Beneath Me,” which talks of the “cold dirges of the baffled.” Not quite it, but I bookmarked the poem anyway.

Later I woke from a dream of wilderness and realized I’d felt this way once before, when Kim and I were briefly lost. Not lost as a metaphor, but lost literally and in some distress, even though we had a map and the means to get out.

Let me explain.

Some years ago, we were hiking at 8,000 feet in the Sierra Nevada. Kim and I had backpacked in the day before and spent the summer night just a few yards from the shore of an alpine lake, whose waters were as blue as an aquarium, and now it was time to hike back out and pick up the Pacific Crest Trail, which would lead through dense forest, saddles still packed with snow, and one stair-stepping descent that was all rock. It would be the same path that we took on the way in, only five or six miles in length, with spectacular views of the Desolation Wilderness.

It was the kind of trail the guidebooks marked as “challenging,” which didn’t seem especially daunting as we’d been hiking a lot in Kansas, with full packs, and our hiking boots were well broken-in. But there were things we did not expect, partly because we were over-confident and partly because things weren’t as the guidebook said they should be.

First, we discovered a mile of this section of the PCT was steep and worth two or three miles of flat prairie. We couldn’t cover nearly the distance we thought we could, and after a few hours the exhaustion of dealing with the terrain, at least for me, left me with little enthusiasm for the view. Second, the mosquitoes — which were supposed to have been at a minimum at the end of June, according to the book — were present in great swarms and seemed unusually large. The deeper in the wilderness we went, the thicker they became, until any stop to rest or eat or do necessary business resulted in a battle against bloodthirsty pests that seemed bent on driving us mad. Kim, who is clever even when under attack, invented a name for these large swarms: These were “panics” of mosquitoes.

So what was meant to be a soul-reaffirming experience — hiking a part of the PCT after having read and re-read “Wild” by Cheryl Strayed — became an exercise in humility. We managed to spend a little time appreciating the beauty of the alpine lake once we arrived there, and Kim shed her boots and cooled her bare feet in the water. Then we ate dinner and pitched our tent and went to sleep in our bags as soon as it was dark. We had decided to get up at dawn and head back down the mountain to be on time to catch the water ferry at the trailhead.

When dawn came, we battled the mosquitoes and packed our gear and set off toward the trail, a quarter of a mile or so to the east. It had been an easy traverse the afternoon before, down a slope with rock cairns leading the way to the lake. Now, we were climbing the slope. The sun had just topped the ridge. The sunlight shot through the trees and illuminated some patches of early morning fog, resulting in a kind of whiteout that rendered the wooded landscape alien. The combination of brilliance and deep shade made for slow walking because it was difficult to see where to put your feet.

Within a hundred yards or so we were lost, no cairns to be found, and though we knew the trail had to be in the direction of the sun, the farther we went the rougher the terrain was. After I stumbled a few times on the rocks, we stopped and I had to admit we were lost. So lost, in fact, that I wasn’t even sure I could retrace our steps back to the lake.

For the first time hiking, I felt fear in the pit of my stomach. We weren’t that bad off. We weren’t miles from the trail. We were well-equipped. But we were lost in the wilderness with no idea of how to get where we needed to be. And the constant panics of mosquitoes made all other discomforts seemingly unbearable.

So we stopped and talked over the best thing to do. I had a topo map, but until the sun got a bit higher it would be difficult to judge our position. It was my first experience hiking directly into the sun. And it was like driving into the sun but worse because there were no visors to lower and no lanes to follow. My trailblazing skills had been tested and found wanting. If we were going to make the water taxi back to the Jeep and South Lake Tahoe and showers and cheeseburgers, we were going to have to do something different.

I reached into the waist pocket of my pack and brought out the hand-held GPS. On the way in I was using it to check the elevation, because the trail was well-marked. I don’t recall now how far off course we were, but it did take some time to backtrack and pick up our route from the day before. Soon we were back on the PCT and, a few hours later, made the water taxi with only minutes to spare.

The feeling of being lost in the brilliant fog of a new day is with me now.

Blinded by torrents of content and afflicted by a panic of cultural discomforts, it might seem as if we are trapped in a societal wilderness with no way out. Yet, we’ve always had with us the tools necessary to determine the path forward. All we have to do is stop and think.

It’s natural to be afraid when faced with uncertainty, but we can’t let the fear overtake us. And unlike my story about being ever so briefly lost in the wilderness, when tomorrow dawns there will not just be one correct path forward but several. The world is made anew each day, as evidenced by the constant stream of headlines, and adjustments to the course will be necessary.

The challenge is to keep pursuing the sometimes-branching path that will lead to the destination that represents the best of what we can hope for ourselves, our country, our world. This is the Constitutional promise of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. It is the fundamental vision of what it is to be an American, to find our place among the powers of the earth, and if we are divided as a country now it’s because we’ve forgotten the politically sacred text that set us upon the path which promises justice and equality for all. The Constitution is the map, not the destination.

Whitman knew the American soul like no other, and in “Leaves of Grass” he celebrated the individual and even sensual nature of our democracy. Its frankness caused some critics to declare it obscene, but time has acquitted Whitman more justly than any court. First published in 1855, and revised and greatly expanded throughout his life, the book defines the American character in vibrant and sometimes lustful terms, but always mindful of democracies big and small.

“I speak the password primeval,” Whiteman writes. “I give the sign of democracy; By God! I will accept nothing which all cannot have their counterpart of on the same terms.”

Whitman, a pacifist who volunteered to care for wounded soldiers during the Civil War, became known during his lifetime as America’s poet. He was our Homer, singing not of the will of the gods but of the will of ordinary Americans. He was so famous that, during the last months of his life, the New York Times ran regular updates on his health.

“Walt Whitman’s diet has been changed,” the Times reported Jan. 2, 1892. “Today he ate two small pieces of squab and drank a little champagne.” The account also gave his pulse at 78, respiration 25.

Whitman died March 26, 1892, of bronchial pneumonia. He was 72.

In the decades that followed, Whitman was so universally admired that “Leaves of Grass” was not only published in a Little Blue Books edition by Socialist publisher E. Haldeman-Julius of Girard but also was widely distributed by the U.S. government during World War II.

If we are to heal the division in America’s soul, the solution must come not only from political action but also from the arts. Whitman’s poetry had the power to bind a nation bloodied by the Civil War. Today there is, somewhere on the streets of New York or Los Angeles or Wichita, Chicago or Atlanta or Topeka, someone who knows the soul as yet unsung of our 21st century America.

Let us find them so their voice may lead us out of the blinding fog.

Max McCoy is an award-winning author and journalist. Through its opinion section, the Kansas Reflector works to amplify the voices of people who are affected by public policies or excluded from public debate. Find information, including how to submit your own commentary, here.

Excerpts or more from this article, originally published on Kansas Reflector appear in this post. Republished, with permission, under a Creative Commons License.