This article was originally published by The Emancipator.

Derrick Williamson says that when the Hardee family promised to give him 40 acres of land in Morgan County, Georgia, in June 2021, he thought his dream of opening an animal sanctuary had come true.

He hewed wood and tilled soil, filled his biblically referenced animal sanctuary, The Way Dynamic Animal Therapy Encounters, with more than 100 animals, including sloths and wallabies, built enclosures, and made improvements — all of which increased the property value. Then, in January 2022, Williamson said Janet Hardee informed him that she decided to sell the land after all. Under the guise of just needing a temporary place to stay, he said the Hardee family proceeded to move into his home on the sanctuary’s grounds.

In acts of macroaggressions and harassment caught on film, the family cursed as they chased him through rooms, banged pots to keep him awake, slammed doors, taunted him about his deceased brother, assaulted him physically, and ultimately ran him off the property. Most of his animals died or were sold off.

The Hardee family has filed numerous counterclaims and restraining orders asserting — among other things — that they have a right to the land.

Janet Hardee and her husband, James, died in February 2025 in a plane crash near Covington Municipal Airport. However, her heirs continue to occupy the land amid the fight over the property. Brad Evans, an attorney for Janet Hardee, told The Emancipator that Williamson’s claim is “without merit” and that his clients assert that as co-company owners “when the property was purchased, the property was deeded by Ms. Hardee to [The Way Dynamic Animal Therapy Encounters ] with the agreement that the property would be deeded out of the company and back to Ms. Hardee at her request.”

The ensuing back-and-forth and ongoing legal actions have upended Williamson’s life.

“I don’t know what’s gonna happen to me next … based off my deed, my property is worth millions of dollars. But yet I have no access to my property, to business, to all those things,” Williamson said.

Williamson’s experience is a glimpse of what Black landowners and farmers have faced for more than a century. They are concerned land dispossession will worsen amid a racist climate of retrenchment on civil rights.

Black farmers have historically endured generations of discrimination in land ownership — ranging from denial of the U.S. Department of Agriculture loans at the federal level to the seizure of land through discriminatory eminent domain policies at the state and local level to outright theft by White neighbors.

Land rights organizations and farmers are worried this historic trend will be exacerbated under the Trump administration as it dismantles policies that have promoted diversity, equity, and inclusion and prosecuted civil rights violations.

The Trump administration has closed civil rights offices at agencies such as the USDA that aimed to enforce equity and protection for farmers of color. Their survival is also threatened by the withdrawal of local food agreements among farmers and the elimination of contracts with the World Food Programme through the U.S. Agency for International Development, in which farmers shipped their produce to countries in need.

President Donald Trump’s tariff war could also disproportionately impact Black farmers, who traditionally run smaller farms and could be less well-positioned to absorb price hikes.

One group that asked not to be named out of fear of retribution in having their federal funding cut by the Trump administration told The Emancipator that if grants for community-based organizations helping Black landowners are frozen it could accelerate land loss. Fear of retaliation could also impact the ability or willingness of those who wish to speak up for Black land rights, the group said.

Rich soil and strange fruit

In June 1921 in Tulsa, Oklahoma, at least 300 people died and 35 blocks were burned to the ground during an attack by White supremacists on the Greenwood District, also known as “Black Wall Street.” The affluent Black community that had flourished with businesses such as banks, hotels, and restaurants was reduced to ash and smoldering embers in less than 24 hours. Many survivors fled and never returned, while others stayed to rebuild with what little they could, with some sleeping in tents.

Two years later, in January 1923, over 30 Black residents in the thriving Rosewood, Florida, community were killed when more than 200 White men attacked and burned the community to the ground — with survivors fleeing for their lives and never to return.

Today, Black land dispossession is more subtle.

Technological development and the rise in mechanization and large factory farming have also disenfranchised, said Dylan Penningroth, professor of law and history at the University of California, Berkeley.

“Many of the forces that drove Black people out of land ownership are the same forces that drove White people out of land ownership,” Penningroth said, adding that some government policies may have tilted the playing field toward large operations.

There were 925,708 Black farmers out of nearly 6.5 million total farmers in the U.S. in 1920, according to the USDA. In 2022, there were 46,738 Black farmers in the country — 1.4% of all farmers in the U.S., according to the agency’s most recent census.

Redevelopment and lack of access to credit through federal housing lending made it especially difficult for Black Americans, including farmers, to retain and obtain land.

Real estate developers often target “heir property owners,” people who inherit land from a deceased person without a will or title, and take over the property through means such as a forced sale. Nearly 70% of all Black homeowners do not have a will or trust, according to an analysis by the Urban Institute released in October 2024. Land loss because of heirs’ property issues is also pervasive among Indigenous communities.

Some heir property owners have difficulty accessing home repair or tax reduction programs, obtaining insurance, or facing disasters — all of which could cause a Black landowner or farmer to lose their land. Black elders on a fixed income also face unsustainable and high tax rates, which could force them to sell their homes or lose them to foreclosure. Property taxes on Black-owned homes are also 10% to 13% higher than White-owned homes, according to an analysis by The Brookings Institution.

Eminent domain is another avenue used to capture Black land.

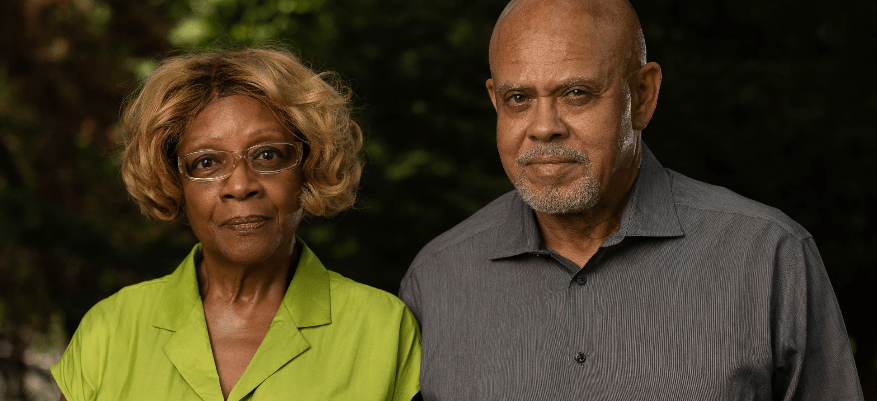

A couple in Sparta, Georgia, Diane and Blaine Smith, has been in a legal dispute for nearly two years over a railroad company that is trying to lay miles of train tracks on land that has been in the family for more than a century. The private company could obtain the land through eminent domain, which allows land to be seized by the U.S. government for public use. A judge has sided with the railroad company, but the Smiths have appealed their case to the Georgia state Supreme Court.

Black land loss has been especially significant in Southeastern states.

The Hogg Hummock community on Sapelo Island, Georgia, a historic Gullah Geechee community — one of the last in the country — is in the midst of a legal dispute over a zoning ordinance. The ordinance could pave the way for construction that residents fear will erase their cultural heritage.

High property values also make it harder for prospective property owners to purchase land. And an increase in property taxes makes it harder to keep one’s land.

Losing roots

While some land dispossession among Black Americans has been driven by racial discrimination, it has also happened when descendants lose interest in retaining the land. Sometimes new generations aren’t interested in farming, Penningroth said.

“If I inherited land or a slice of land back home in Virginia, what would I do with it? I don’t know. I live in California. I don’t know the first thing about farming,” he said. “So, part of the story may have to do with Black people’s own thinking about farming.”

He also said, “There’s no magic bullet solution to Black land loss. … These things are enormously complicated, sedimented historically complex phenomena. They built up over decades, if not centuries.”

Reclaiming the soil

One way Black Americans can retain their ancestral rights to roots and soil passed down through families is through knowledge, organizations say.

Visit those parcels of land “in the country,” those plots that older relatives tell stories about — even if you don’t live close. Consider how the family wants to see the land developed and retained in 20 years and take steps to make that happen, land rights experts said.

Land rights organizations and farmers say there must also be legislative action and policies, such as an adoption of the Uniform Partition of Heirs Property Act, which has been enacted in more than 20 states and aims to protect against the loss of land..

Young people who are interested in farming should be intimidated by what is happening politically, Jewel Bronaugh, former deputy secretary of agriculture, said last week during a forum.

“I don’t want you to be afraid. Don’t be afraid of all the things that you hear spinning in the air,” Bronaugh said. “First of all, we’ve been here before. This is not the first attack on anything that we’re seeing right now. …We have survived and we’re better off, but we need your voices to carry us forward.”

For his part, Williamson told The Emancipator he is also going to ensure that others do not face the same outcome he did. He has held meetings with other families who he said are facing land loss in other states.

“I’ll fight to the last breath for my land, for my animal family,” he said. “In the meantime, I’m gonna continue to fight to help people.”

Learn more about third-party content on ZanyProgressive.com.