As long as the tools of democracy remain intact, writes Max McCoy, we have a chance of coming back from this outrage to democracy. (Max McCoy/Kansas Reflector)

Since Nov. 5 I’ve been feeling like old Doremus Jessup after the election of Buzz Windrip, nursing his wounds in a study cluttered with books and the artifacts of a life of curiosity, including arrowheads and a microscope.

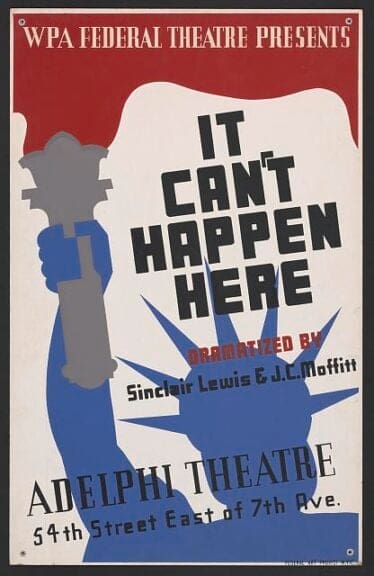

Jessup is the protagonist of the 1935 Sinclair Lewis novel “It Can’t Happen Here.”

Doremus is a sincere but indolent journalist and confirmed sentimental liberal in his 60s who watches fascism capture American government from within. The presidential candidate who whips the voting public into a populist frenzy of democratic abrogation is Sen. Berzelius Windrip, a flag-waving Bible-thumping yahoo inspired by Huey Long but who is a ringer for political charlatans both past and present.

“It Can’t Happen Here” is a great book but not a good one. That is, Lewis wrote it in haste because he saw the rise of American fascism in the 1930s and knew the message he wanted to get across to the widest possible audience, that authoritarianism is most likely to come wrapped in red, white and blue. That is what makes the novel great. This urgency to complete the book, however, introduced literary flaws that make it a lesser book than “Babbitt” or “Elmer Gantry.”

But that should not trouble us here.

The point is that Windrip wins election to the presidency on a campaign aimed at “the Forgotten Man.” Among his 15 campaign pledges are those promising to revoke the vote for Black people and to bar women from holding any job other than nurse or hairdresser so that they may devote their time to the rearing of children. One of the pledges is worth quoting in its entirety.

“Believing that only under God Almighty, to Whom we render all homage, do we Americans hold our vast Power, we shall guarantee to all persons absolute freedom of religious worship,” the Windrip pledge says, “provided, however, that no atheist, agnostic, believer in Black Magic, nor any Jew who shall refuse to swear allegiance to the New Testament, nor any person of any faith who refuses to take the Pledge to the Flag, shall be permitted to hold any public office.”

Upon the inauguration of Windrip as president, Congress would be needed only in an advisory capacity and the Supreme Court would have no jurisdiction to declare the actions of the president unconstitutional.

Our journalist protagonist watches in horror as Windrip ascends to power. His adviser and celebrity surgeon, one Doc Macgoblin, writes the words for a campaign tune that is the American equivalent of the Nazi’s Horst Wessel song. There is even a rally at Madison Square Garden, at which Doremus notes the “murderous temper” of the crowd. The enemies are the elites, the liberals, the professors, the journalists.

“Doremus Jessup … could not explain (Windrip’s) power of bewitching large audiences,” Lewis writes. “The senator was vulgar, almost illiterate, a public liar easily detected, and in his ‘ideas’ almost idiotic, while his celebrated piety was that of a traveling salesman for church furniture.”

After Windrip’s election, Doremus says to hell with it all and retreats to his study to do nothing but read. He intends to read all the classics he’s been meaning to most of his life, but finds little relief in books.

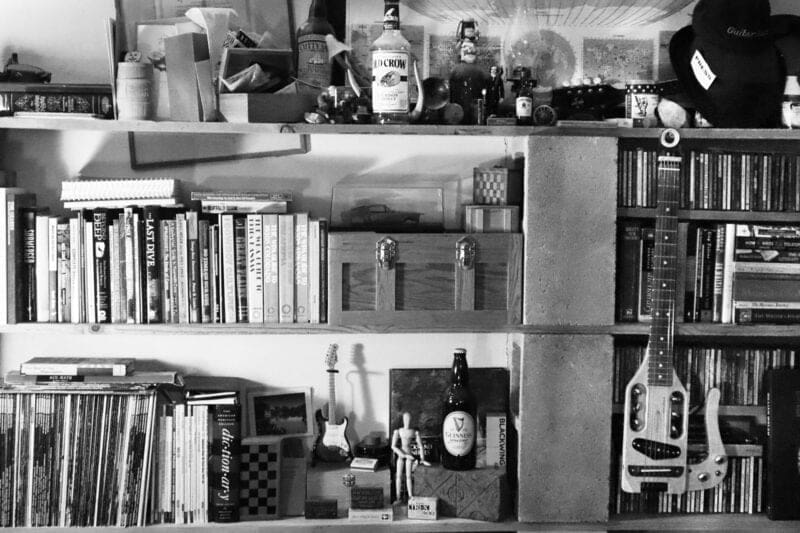

I am of a similar temperament to the fictional Doremus, and my very real and quite messy office on Constitution Street is filled with books and artifacts of a life of curiosity. There is a shelf behind my battered writing desk which contains, among other things, several Little Blue Books from the Haldeman-Julius Publishing Company of Girard, Kansas. I also have, from garage sales, a few of the printing blocks used to create them, notably the frontispiece to No. 1402, Clay Fulks’ “How I Went to the Devil.” There are guitars and amplifiers and an oscilloscope. An old mandolin a friend gave me is on the top shelf, behind a row of empty beer bottles I’ve kept that were shared during special occasions with my wife, Kim.

None of the stuff in my office has helped me since Nov. 5.

I had intended for this column to be about other dystopian novels, including Philip K. Dick’s “The Man in the High Castle” or Christopher Brown’s “Tropic of Kansas.” I was particularly keen to discuss the latter, and I may at some point in the future, but the more I thought and tapped out false starts on the keyboard the more I realized that there was really only one dystopian novel to talk about at this moment: “It Can’t Happen Here.”

Because it has.

I feared it would, not trusting in the pundits and the pollsters to accurately know the temper of the electorate. But what has shocked me is the depth of the self-inflicted wound, that the popular vote went for a man who was a clear threat to democracy itself. We now stand on the threshold of an American oligarchy, where money and influence are valued over competence and expertise. And we have only ourselves to blame.

The pundits — those who were so wrong in reading the mood of the nation — are now engaged in a kind of game to see who can make the most palatable argument for why America’s first Black woman to run for president lost. Here’s a roundup of the leading theories, which are mostly variations on how Democrats lost touch with the working class and failed to understand what the price of eggs had to do with anything. But such hand-wringing and finger-wagging is just an attempt to avoid the most likely answer to the question of why Americans chose a convicted felon, liar, and sexual predator over an accomplished and highly competent Black woman.

Racism and misogyny had their thumbs on the scale.

When will America be ready to elect a woman president? I don’t know. Neither does anyone else. It will be whenever we grow out of our political adolescence, I suspect, when there is another candidate as qualified as Harris, and when questions of identity are less important than character.

What I know for certain is that we are in for a tough fight ahead.

For the first time, I find myself in a country where the popular vote rejected the idea of democracy — by exercising democracy — in favor of something else. Whether this represents a momentary blip or a seismic shift is too soon to tell, but it moves me even further from the center than I was before.

I have felt lonelier since Nov. 5 than I ever remember feeling before — even though about half of the electorate, some 73 million people, saw things as I did. It is important to keep reminding ourselves, those of us who voted against fascism, that we are not in fact alone.

We must continue to be authentic selves, true to the values and the traditions that made us, or risk becoming lost in turmoil and hate. We must continue to stand up for those who need us most. The aftermath of the election has made me fear for those individuals who were already at risk of political oppression — racial and religious minorities, the LGBTQ+ population, and free thinkers of all stripes.

And like Doremus Jessup, it makes me worry about the future of journalism.

I was just a teenager when I got my first reporting job, phoning in election totals from the Cherokee County Courthouse at Columbus in southeast Kansas to the old News Election Service. As the numbers came in on election night, about every 30 minutes I would call a collect number and read updated results. These numbers were fed into a computer somewhere that kept running totals for the service’s five sponsors, including the major television networks, the Associated Press and UPI.

It wasn’t difficult work but it did require one’s presence at the local clerk’s office and the ability to keep numbers straight on a paper grid. What I remember most is how much everyone smoked while waiting on the results. The experience was an indispensable introduction to politics and how the gears of American democracy turn at the local level. I couldn’t even be called a reporter, because I was only relaying information, but I was so proud of my minor contribution to journalism that I kept my NES credentials for years.

Some years later I got a real reporting job, a full-time one, covering the cop shop at a little daily in southeast Kansas that some people outside the state mistakenly insisted on calling “The Morning Star.” There is no such newspaper in Kansas, but I have always thought there should be, as it conjures the promise of dawn.

I thought about those early days in journalism this year as I waited for Election Night returns at the Lyon County Courthouse. The results were tabulated by machine, and there was no thick haze of cigarette smoke, but otherwise there was a similar feel to the elections I used to cover years ago. I particularly liked watching the sacks of ballots being carried in the entrance of the courthouse from the polling places.

As long as the tools of democracy remain intact — the ballots and the polling places and voter protection and fair elections — we have a chance of coming back from this outrage to democracy. So much is at stake it is imperative to keep hope alive. We must act as if our actions will be judged not today, or tomorrow, but 100 years in the future. Because they will.

Spoiler alert.

What happened to old Jessup in “It Can’t Happen Here?”

He continues to write editorials critical of Windrip’s regime and is eventually sent to an internment camp. But he escapes and flees to Canada with the help of the “New Underground,” a resistance movement named for the Underground Railroad. The country breaks apart and a civil war ensues.

But that can’t happen here. Right?

Max McCoy is an award-winning author and journalist. Through its opinion section, the Kansas Reflector works to amplify the voices of people who are affected by public policies or excluded from public debate. Find information, including how to submit your own commentary, here.

Excerpts or more from this article, originally published on Kansas Reflector appear in this post. Republished, with permission, under a Creative Commons License.

See our third-party content disclaimer.