The United States deported 238 Venezuelan men on three flights to El Salvador on March 15, 2025, claiming that they were members of the Tren de Aragua gang that originated in Venezuela. Their tattoos were said to have determined their membership in Tren de Aragua.

Immigration officials have said that tattoos were not the sole criteria used when deciding whom to deport; however, a government document showed that officials relied on tattoos and clothing to determine gang membership.

A lawyer for Jerce Reyes Barrios, a professional soccer player who is among the Venezuelans deported to El Salvador, says the government detained and deported her client because he has a tattoo of a soccer ball with a crown on top, which resembles the logo of his favorite soccer team, Real Madrid. The tattoo and a photograph of Barrios making a hand sign that means “I love you” in sign language are the only two pieces of evidence the government has presented of his gang ties, according to the lawyer.

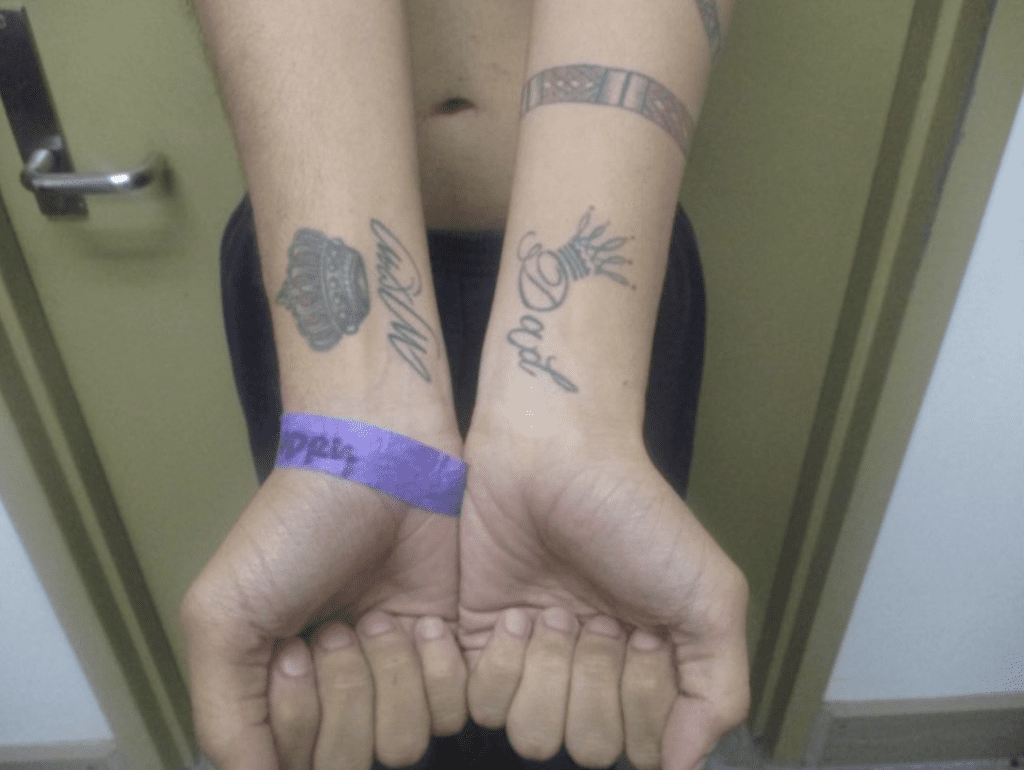

Meanwhile, deported Venezuelan makeup artist Andry José Hernández Romero has a tattoo of a crown on each wrist, one with “Dad” and one with “Mom” written next to each crown. Immigration authorities indicated in his file that these tattoos were “determining factors to conclude reasonable suspicion” of his membership in the Tren de Aragua gang. Some government sources list crowns as a tattoo common for Tren de Aragua members, but other government sources cast doubt on that claim.

Whether or not the Trump administration used tattoos as a sole criteria for deportation, I’ve found in my own research that simply using tattoos as any sort of criteria can lead law enforcement astray.

In 2023, I analyzed the reliability of tattoos as markers of gang membership in the Washington Law Review.

The bottom line: While many people in gangs have tattoos that demonstrate their membership, many people who have absolutely no gang ties also get similar tattoos.

Relying on them to determine gang membership has led to systematically misidentifying people as gang members – particularly as tattoos have become more popular.

There are some types of tattoos that can be especially misleading.

Geographic origins

In 2017, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement detained Daniel Ramirez Medina, who was lawfully in the United States under the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, or DACA. The government attempted to strip his status and deport him, claiming he was a gang member due to a tattoo that read “La Paz BCS.” La Paz is the capital of the Mexican state Baja California Sur, which is abbreviated “BCS.” The only evidence of gang membership that ICE agents presented in immigration court was this tattoo.

But they overlooked the fact that tattoos depicting the names or area codes of hometowns or countries of origin are a common way for people to honor where they came from.

This is particularly the case for people who migrate or move away from their homelands. For example, tattoos of “503” and “504” – the country codes used to dial El Salvador and Honduras, respectively – have been relied upon to allege gang membership, even as many people who have these tattoos deny any gang ties and have no criminal records. Law enforcement has also relied on tattoos of the words “Mexican,” “Chicano” or “Brown Pride” as evidence of gang membership.

Some gangs, such as the Mexican Mafia, include a reference to nationality in the name of the gang. And in the U.S., street gangs are often based in specific neighborhoods, with many gangs incorporating the city or street where they’re based into gang names and associated tattoos. For this reason, tattoos celebrating a city or country can only lead to confusion.

Tattoos of Mayan or Aztec images have also been used to designate people as gang members, even though these tattoos are clear expressions of cultural identity and do not necessarily have any nexus to gang membership. While some gangs do use specific Aztec symbols to identify members, it’s virtually impossible to distinguish a tattoo of cultural or geographic significance from a tattoo indicating gang association.

In the case of Medina, U.S. District Judge Ricardo S. Martinez, a George W. Bush appointee, ordered that his DACA status remain in place and that he be protected from deportation because ICE’s “conclusory findings” that he was a gang member were “contradicted by experts and other evidence.” Furthermore, an immigration judge who reviewed all the evidence had already concluded that he was not in a gang.

Martinez was clearly disturbed by ICE’s claims, writing, “Most troubling to the Court is the continued assertion that Mr. Ramirez is gang-affiliated, despite providing no evidence specific to Mr. Ramirez to the Immigration Court in connection with his administrative proceedings, and offering no evidence to this Court to support its assertions four months later.”

Religious imagery and pop culture

Tattoos of popular Catholic religious images, such as the Virgin of Guadalupe, praying hands and rosaries, have also been used to label people as gang members, a move that would seem to be clearly overbroad.

While some gang members may be Catholic, no one would even try to allege that all Catholics are gang members. At least one of the deported Venezuelan men had a tattoo of a rosary, along with tattoos of a clock and the names of his mother and niece with crowns atop the text.

Tattoos have also become an important way for people to celebrate popular culture. Tattoos of a woman’s lips, for example, have become popular among gang members and non-gang members alike. A number of professional athletes, including soccer phenom Lionel Messi, have tattoos of their partner’s lips. However, this is also a tattoo law enforcement uses to categorize people as gang members.

According to the Texas Department of Public Safety, tattoos of stars on shoulders, crowns, firearms, grenades, trains, dice, roses, tigers and jaguars are common among members of Tren de Aragua.

The issue, of course, is that these symbols are also popular among people with no connection to the gang.

Imprecise methodology

Understanding the problem really comes down to math. While it may be true that many gang members have tattoos of the images listed above, it is also true that many non-gang members have similar tattoos.

The Bayesian mathematical approach involves making inferences about probabilities based on available information. The probability that a gang member has a certain tattoo isn’t the same as the probability that an individual who has a certain tattoo is a gang member.

The U.S. government seems to be wrongfully equating the two.

Writing about the broader problems of discerning gang membership in 2009, sociologist David Kennedy argued that the law’s inability to devise rules “that clearly distinguish a gang and a football team, or a gang member and his mother” suggests that taking “legal action, based on imprecise language [is] something of a problem.”

This problem becomes magnified when there’s no due process for the accused – which is exactly what happened to the Venezuelan men whisked off to El Salvador.

The article featured in this post is from The Conversation and republished here under a Creative Commons License. Read the original article. Learn more about third-party content on ZanyProgressive.com.