Misinformation has always been an issue but it seemed to become a much bigger problem when Donald Trump arrived in the political sphere. His claims of “fake news,” his involvement in spreading social media posts coming from Q’anon followers, and of course—The “Big Lie.” In his first term as President, Trump lied 30,000+ times.

He tends to exaggerate everything (”…more than anyone has ever seen”, “…this has never happened in the history of the country” “…my crowd was bigger than the crowd Martin Luther King, Jr. had at his speech…”) and he will lie rather than admit he was wrong about something (changing the trajectory of a hurricane on the map with a Sharpie to include Alabama after he falsely claimed it would affect Alabana).

After losing the 2020 election, Donald Trump began spreading misinformation like wildfire. He would see something posted about election fraud and share it on social media even if it was obviously untrue. His lies and misinformation caused the distrust in our elections by some Americans, even though Attorney General Bill Barr said the fraud claims were “bullshit” and the Director of CISA, a Republican appointed by President Trump, said it was “the most secure election” we’ve ever had in this country.

Republican Mayors, Governors, Secretaries of State, legislators, and election officials refuted the election misinformation and explained what was actually happening in videos where Trump claimed fraud was taking place.

Unfortunately, the right-wing media ecosystem spread the same lies and misinformation coming from the President and Republican members of Congress. Although there were trusted Republican voices correcting the lies and misinformation about the 2020 election, only mainstream and independent media sources reported it, not Conservative news sources.

Misinformation in Media

Thanks, in part, to Trump’s “fake news” claims. This is still true today and in my opinion, is the main reasons for the polarization in our politics. We have members of two political parties that live in different realities because of misinformation spread by outlets where Conservatives tend to go for news.

The combination of Q’anon and Conservative media misinformation caused an entire group of people (MAGA) to distrust news from reputable sources, distrust our election systems, the volunteers who worked in polling places and vote counting centers, and after he politicized a global pandemic, Trump caused the distrust of nurses, doctors, and other medical professionals, the experts at the CDC, WHO, and NIH, scientists, and vaccines.

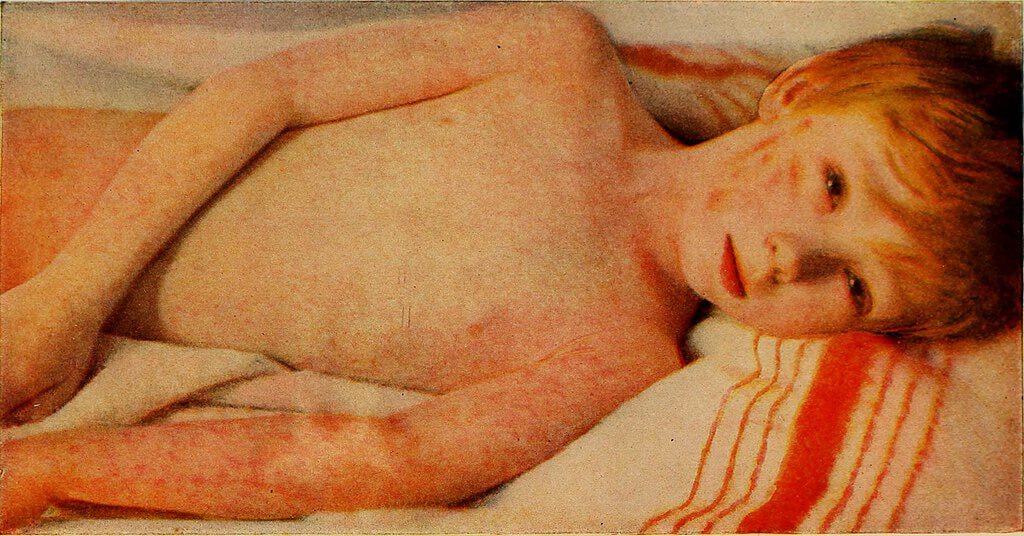

We are currently seeing the damage caused by anti-vaccination misinformation in the Measles outbreaks and deaths caused by unvaccinated children in communities where the overall vaccination rate is low. We had already eradicated Measles using the vaccine to create “herd immunity.”

From an article on the World Economic Forum website written by Alex Edmans, Professor of Finance, describes why Americans believe misinformation:

Key Points:

✔️ Confirmation bias is the temptation to accept evidence uncritically if it confirms what one would like to be true.

✔️ Black-and-white thinking is another form of bias that entails viewing the world in binary terms.

✔️ can overcome these biases by asking simple questions and thinking critically.

Contents

We’ve heard these phrases enough times that they should be in our DNA. If true, misinformation would never get out of the starting block. But there are countless examples abound of misinformation spreading like wildfire.

This is because our internal, often subconscious, biases cause us to accept incorrect statements at face value. Nobel Laureate Daniel Kahneman refers to our rational, slow thought process — which has mastered the above three phrases — as System 2, and our impulsive, fast thought process — distorted by our biases — as System 1. In the cold light of day, we know that we shouldn’t take misinformation at face value, but when our System 1 is in overdrive, the red mist of anger clouds our vision.

Confirmation Bias

One culprit is confirmation bias – the temptation to accept evidence uncritically if it confirms what we’d like to be true, and to reject a claim out of hand if it clashes with our worldview.

Importantly, these biases can be subtle; they’re not limited to topics such as immigration or gun control where emotions run high. It’s widely claimed that breastfeeding increases child IQ, even though correlation is not causation because parental factors drive both.

But, because many of us would trust natural breastmilk over the artificial formula of a giant corporation, we lap this claim up.

Confirmation bias is hard to shake. In a study, three neuroscientists took students with liberal political views and hooked them up to a functional magnetic resonance imaging scanner. The researchers read out statements the participants previously said they agreed with, then gave contradictory evidence and measured the students’ brain activity.

There was no effect when non-political claims were challenged, but countering political positions triggered their amygdala. That’s the same part of the brain that’s activated when a tiger attacks you, inducing a ‘fight-or-flight’ response.

The amygdala drives our System 1, and drowns out the prefrontal cortex which operates our System 2.

Confirmation bias looms large for issues where we have a pre-existing opinion. But for many topics, we have no prior view. If there’s nothing to confirm, there’s no confirmation bias, so we’d hope we can approach these issues with a clear head.

Black and White Thinking

Unfortunately, another bias can kick in: black-and-white thinking. This bias means that we view the world in binary terms. Something is either always good or always bad, with no shades of grey.

“To pen a bestseller, Atkins didn’t need to be right. He just needed to be extreme. ”— Alex Edmans, Professor of Finance, London Business School

The bestselling weight-loss book in history, Dr Atkins’ New Diet Revolution, benefited from this bias. Before Atkins, people may not have had strong views on whether carbs were good or bad. But as long as they think it has to be one or the other, with no middle ground, they’ll latch onto a one-way recommendation. That’s what the Atkins diet did. It had one rule: Avoid all carbs.

Not just refined sugar, not just simple carbs, but all carbs. You can decide whether to eat something by looking at the “Carbohydrate” line on the nutrition label, without worrying whether the carbs are complex or simple, natural or processed.

This simple rule played into black-and-white thinking and made it easy to follow.

To pen a bestseller, Atkins didn’t need to be right. He just needed to be extreme.

Overcoming Our Biases

So, what do we do about it? The first step is to recognize our own biases. If a statement sparks our emotions and we’re raring to share or trash it, or if it’s extreme and gives a one-size-fit-all prescription, we need to proceed with caution.

The second step is to ask questions, particularly if it’s a claim we’re eager to accept. One is to “consider the opposite”. If a study had reached the opposite conclusion, what holes would you poke in it? Then, ask yourself whether these concerns still apply even though it gives you the results you want.

Take the plethora of studies claiming that sustainability improves company performance. What if a paper had found that sustainability worsens performance? Sustainability supporters would throw up a host of objections. First, how did the researchers actually measure sustainability? Was it a company’s sustainability claims rather than its actual delivery? Second, how large a sample did they analyze?

If it was a handful of firms over just one year, the underperformance could be due to randomness; there’s not enough data to draw strong conclusions. Third, is it causation or just correlation? Perhaps high sustainability doesn’t cause low performance, but something else, such as heavy regulation, drives both.

Now that you’ve opened your eyes to potential problems, ask yourselves if they plague the study you’re eager to trumpet.

A second question is to “consider the authors”. Think about who wrote the study and what their incentives are to make the claim that they did. Many reports are produced by organizations whose goal is advocacy rather than scientific inquiry.

Ask “would the authors have published the paper if it had found the opposite result?” — if not, they may have cherry-picked their data or methodology.

In addition to bias, another key attribute is the authors’ expertise in conducting scientific research. Leading CEOs and investors have substantial experience, and there’s nobody more qualified to write an account of the companies they’ve run or the investments they’ve made.

However, some move beyond telling war stories to proclaiming a universal set of rules for success – but without scientific research we don’t know whether these principles work in general.

A simple question is “If the same study was written by the same authors, with the same credentials, but found the opposite results, would you still believe it?”

Today, anyone can make a claim, start a conspiracy theory or post a statistic. If people want it to be true it will go viral. But we have the tools to combat it.

We know how to show discernment, ask questions and conduct due diligence if we don’t like a finding. The trick is to tame our biases and exercise the same scrutiny when we see something we’re raring to accept.

This article is adapted from May Contain Lies: How Stories, Statistics, and Studies Exploit Our Biases – and What We Can Do About It (Penguin Random House, 2024).