During the fall of 1886, both jail cells in the Jefferson County Courthouse at Oskaloosa were occupied by a pair of newlyweds: 16-year-old Lillian Harman and her husband, Edwin C. Walker.

Their crime?

Having been married without benefit of clergy or marriage license at the home of Lillian’s father on Sept. 19 in nearby Valley Falls. The “free lovers” had declared themselves unfettered by church or state and had spent just one night together before a family member swore out an affidavit against them, resulting in their arrest.

Although Lillian Harman was not as famous as other sex radicals in Victorian America, her prosecution resonates today regarding equality, free speech and the role of the state in determining what individuals can do with their bodies.

Her father, Moses Harman, who had officiated at the wedding, was a leading anarchist, feminist and free thinker who published a newspaper, provocatively titled “Lucifer: the Light-Bearer,” that scandalized not just the community of tiny Valley Falls but invited the scrutiny of law enforcement. Among those who took notice of the birth control information and other content of the newspaper was self-appointed moral censor and special postal agent Anthony Comstock, who waged a long and ultimately successful campaign to throw Moses Harman and others in federal prison for the material they published. At least 15 individuals, hounded by Comstock, are believed to have committed suicide. Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw, in a 1907 letter, declared: “The reason I do not go to America is because I am afraid of Mr. Anthony Comstock and being imprisoned like Mr. Moses Harman.”

Moses Harman is one of those figures in Kansas history who, once encountered, jars us out of what we think we know about our past. It wasn’t all sunflowers, cattle drives and Bleeding Kansas. Harman’s evolution was from schoolteacher to abolitionist to anarchist. Anarchism in the 1880s, at least before the Haymarket Bombing caused it to be popularly associated with terrorism, placed an emphasis on individual sovereignty and opposed any attempts to limit autonomy. In some ways, these ideals are reflected in the modern Libertarian party. And although Harman typically advocated nonviolent change, he once wrote a column in which he praised dynamite as a way to achieve political change.

But Harman was also a feminist and an advocate of free love, when that term meant something different than it does today, and he eventually became a leading voice in the eugenics movement. Eugenics — the scientifically unsound theory that selective breeding can improve desirable traits in human populations — was generally accepted in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It wasn’t until after the Nazis used it to persecute and murder individuals they considered inferior that eugenics fell out of the scientific mainstream.

Moses Harman was a believer in the power of fact and came up with his own dating system, the “Era of Man,” which began the year after Italian philosopher Giordano Bruno was burned at the stake for heresy by the Inquisition in 1600. Editions of Lucifer published at the time of Lillian Harman and Walker’s marriage carry the confusing date of “E.M. 286,” a count of the years since free-thinking Bruno’s execution.

Both Lillian and Walker worked for Lucifer as well; she as a compositor and Edwin as an editor and roving speaker on anarchy and related topics, including opposition to conventional marriage, which the Luciferians saw as sex slavery for the woman. As publisher, Moses Harmon set the tone for the publication, including the title.

First named the “Kansas Liberal,” Moses Harman changed the name of his publication in 1883. As scholar Hal D. Sears noted in his 1977 book, “The Sex Radicals,” the name change was an attempt to escape regionalism and embrace a bigger vision.

“As the herald of dawn after the black night of the Age of the Gods,” Sears wrote, “the morning star, Lucifer, would appropriately shine forth from the Kansas plains.”

It was also likely chosen for its diabolical overtones. Lucifer, according to Christian theology, was once favored by God among all the angels but was cast out for leading a rebellion.

A subscription to Lucifer cost $1.25, or more than $40 in today’s money. The weekly had a few hundred subscribers, according to Sears, but it really was a shoestring operation, and having two of its employees in jail created extra work for Moses Harman and the rest of the staff. In the weeks before the “autonomistic marriage,” the paper had published, unedited, a series of letters describing horrific situations, including one about a husband who had forced himself upon a wife still healing from the complicated childbirth. The letters may have influenced Harman father and daughter, and Walker, to test the marriage laws of Kansas. Although Moses Harman had repeatedly stressed that marriage should be a private affair between individuals, the marriage of Lillian and Edwin — and the aftermath — was carefully chronicled in “Lucifer.”

The vows exchanged during the ceremony were not to love, honor and obey, but rather a list of expectations with the caveat that either party could terminate the relationship. Either was free to reject the advances of the other. The care of any children from the union (and there would be one) was agreed upon. And Lillian would keep her maiden name.

Since first reading about this marriage years ago, I have had questions. Foremost is whether a 16-year-old girl, raised in a household with an eccentric and larger-than-life father, could resist the ideas that were coin for the “Lucifer.” It would be only natural for her to adopt her father’s political and social views; Lillian’s own mother was dead, and her father had brought her to Kansas, where she grew up in the family business of iconoclasm. What teenager could resist a doctrine of unfettered individual freedom?

Then there is the matter of Edwin Walker, who had a former wife and two children elsewhere in Kansas, according to Sears. He was 36 years old, more than twice Lillian’s age. In addition, he was an editor at “Lucifer,” outranking her.

Whatever the case, after the wedding ceremony the couple retired to a bedroom. In the morning, having presumably consummated the union, a step-brother of Lillian’s reported the unlicensed marriage to the local police, and the couple was arrested.

The arrest was widely reported in the local press and eventually made its way to the national and international papers. If there was another case of “free lovers” being arrested in America, nobody could think of it. There were others who advocated love without chains, such as Victoria Woodhull — a spiritualist, suffragist, and the first woman to run for president, in 1872 on the Equal Rights Party. In America in the late 19th Century, there was a curious synergy among those who believed in trance mediumship, advocated for free love, and supported women’s suffrage.

The marriage case created an immediate sensation. In Valley Falls, according to Sears, one of the reasons the step-brother may have alerted authorities was to save the couple from a local mob of objectors. The local and state papers were quick to condemn the marriage, presumed guilt and urged maximum penalties.

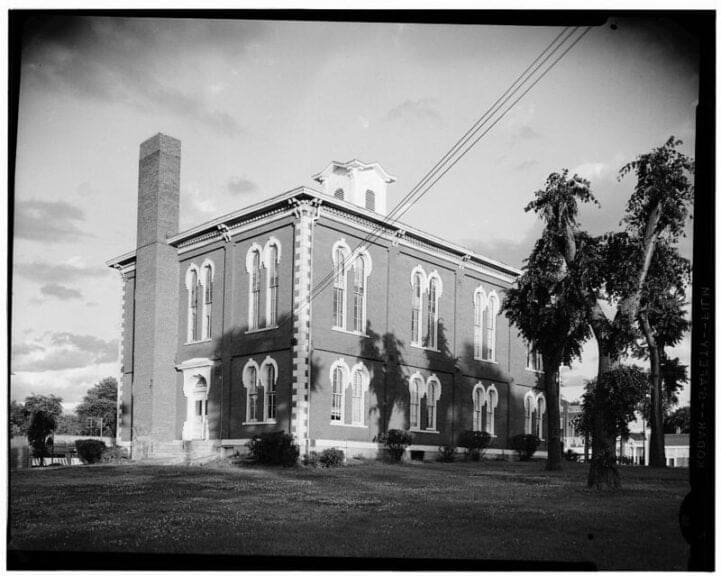

Meanwhile, the pair were being held on $1,000 bond, first in the Jefferson County Jail and later in the Shawnee County Jail at Topeka. Unable to make bail or to persuade wealthy supporters of their newspaper to do so, they spent weeks behind bars. The Topeka jail was particularly objectionable, Walker wrote in a dispatch to the “Lucifer,” full of rats, rough characters and precious little privacy for his teenaged wife.

The trial was held Oct. 14, 1886, before Judge Robert Crozier.

The jury quickly brought in a guilty verdict. Crozier sentenced Walker to 75 days in jail and Lillian to 45. They were also ordered to pay court costs, which they refused, resulting in the couple being kept in jail after they had served their allotted sentences.

National sympathy began to turn in favor of the couple being held in jail on a conviction that seemed increasingly absurd. As explained by Charles J. Reid Jr. in a 2012 issue of the Michigan Journal of Gender and Law, the conviction had tied the law in knots. Even though common law marriage was legal in Kansas, the couple had been convicted of living as man and wife without benefit of a license or officiating clergy. From the beginning, Reid says, it was clear the “free love” marriage was meant to be a test case — and presaged arguments that continue today.

“Freedom of Choice,” Moses Harman wrote, “is a natural right.”

The couple appealed, and the case went to the Kansas Supreme Court, which sidestepped the issue of whether the Kansas Marriage Act of 1867 and its requirement of a license effectively ended the recognition of common law unions. The Kansas Supreme Court affirmed the lower court decision.

Lillian Harman and Edwin Walker were freed from jail April 4, 1887, after Moses Harman paid court costs of $113.80. At the time, Moses himself was under indictment by a federal grand jury in Topeka on 270 counts of sending obscene material through the mail. It was just the first of several prosecutions of Harman under the Comstock laws.

In 1890, Moses Harman moved the publication of Lucifer to Topeka and, in 1896, to Chicago. In 1906, at the age of 75, after another obscenity conviction, he was sentenced to hard labor at the penitentiary at Joliet, where he broke rocks during an Illinois winter, according to Sears. Transferred to the federal pen at Leavenworth, he was released in 1907.

Moses Harman died in 1910, after having moved his operation to Los Angeles.

Anthony Comstock died of pneumonia in 1915, age 71.

The Comstock Act outlived them both.

On the books since its passage in 1873, the enforcement of the act has been increasingly limited in scope by Congress and decisions by the U.S. Supreme Court. The defanging of Comstock began when a federal judge in 1933 declared the James Joyce novel “Ulysses” was not obscene.

Sending birth control information through the postal service hasn’t been a crime in more than 50 years. Decisions about what constitutes obscenity, notably Roth in 1957 and Miller in 1971, have made it more difficult to declare pornographic materials obscene. Even so, Comstock still has provisions making it illegal to distribute materials “for producing abortion” through the mail, even though enforcement was stayed after 1973’s Roe v. Wade.

Now that the constitutional right to an abortion has been overturned by the Dobbs decision, the Comstock Act may again be used to restrict access to reproductive rights material. In the Project 2025 playbook for the new conservative administration, Comstock is cited as a means of limiting access to abortion pills.

“Following the Supreme Court decision in Dobbs, there is now no federal prohibition on enforcement of (Comstock),” the 2025 document says. “The Department of Justice in the next conservative administration should therefore announce its intent to enforce federal law against providers and distributors.”

The urge to control women’s bodies, as Lillian Harman knew, is powerful. It often comes wrapped in religious dogma, reinforced by patriarchal institutions, and abetted by the shaming of those who would take back control of their own selves. It’s disturbing that Moses Harman flirted with the idea of using dynamite and fell for the pseudoscience of eugenics, but it’s tragic that he was sentenced to hard labor in a federal penitentiary for exercising his Constitutional right of free speech.

As we stand at the border of a political Dark Age that is likely to reshape Constitutional law, it is helpful to remember Moses and Lillian Harman and others, such as birth control activist Margaret Sanger, who were targets of legalized persecution. We are likely to be confronted by such Comstockery, a word coined by playwright Shaw, once more. The best dynamite against oppression is the truth widely spoken. Speak now, while we can.

Max McCoy is an award-winning author and journalist. Through its opinion section, the Kansas Reflector works to amplify the voices of people who are affected by public policies or excluded from public debate.

Excerpts or more from this article, originally published on Kansas Reflector appear in this post. Republished, with permission, under a Creative Commons License.

See our third-party content disclaimer.