You know when the winter country has arrived in Kansas because the sky at midday is a shade of blue that throbs with light but no warmth. The shameless trees are studded with diamonds that flare in the sunlight, the long grass is matted with snow, and the geese are lords of the frozen fields. The very ground sends a chill right up through your boots to squeeze your spirit in a grip that makes you long for the golden days of summer.

Because summer is half a year away, you will settle for a favorite chair and a hot cup of tea, if you are lucky enough to have such a refuge. If you are uncommonly lucky, you will have someone who cares about you enough to help you off with your boots at the door when the workaday chores are done. This someone — my someone, Kim — will hold the work light while you lie with your back on the cold kitchen floor and peer up into the plumbing beneath the sink, wrenches in hand, while you try to puzzle out why the garbage disposal is backflowing into the dishwasher. Later, there will be a reward in a warm bowl of brown beans from a pot that has been cooking all day.

These are the things that make the winter country bearable, at least for me.

I have heard of those who revel in the thought of frigid weather, but such delights are alien to me. While I have often written of the joy found in nature, I am strictly a three-season enthusiast. Although I have sometimes camped in the snow in single-digit temperatures in the name of research for some book or another, I do not enjoy it.

I have a friend who I’ll call George, because that’s his name, who seems absolutely down with all of this winter stuff, but I suspect there is something deeply wrong with him. He probably thinks the same of me, as I anxiously await the return of spring.

As I write this — it’s before dawn Thursday morning, Jan. 9 — the temperature here at Emporia in east central Kansas is a fitting 13 degrees. It was no degrees the night before. It’s not snowing, but there is still a few inches of the filthy white stuff from the storm that began last weekend. I was particularly disappointed because otherwise reliable sources had been predicting a mild winter, and then we got walloped by a major winter storm.

By the time it was done, Topeka had received more than a foot of snow. Interstate 70 from the Missouri state line to Hays, in western Kansas, was closed. By Sunday afternoon, every highway in the northeastern quarter of the state was closed, according to the Kansas Department of Transportation online map.

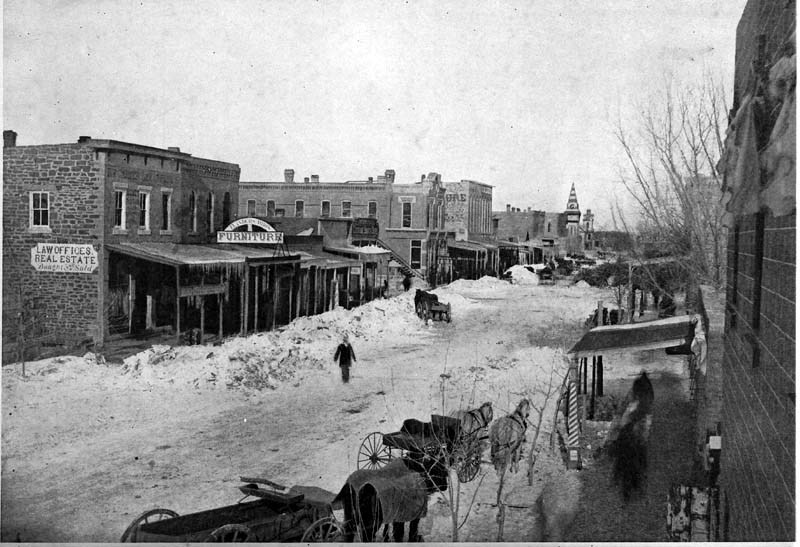

It was a historic storm, with single-day snowfall records broken across the region, followed by wind chills in the negative double digits. It all got me to thinking about what is considered the worst blizzard in Kansas history, in January 1886.

A remarkable account is found in the February 1930 issue of the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. It was written by B.R. Laskowski of the U.S. Weather Bureau, Topeka. The bureau was the forerunner of the National Weather Service.

“Following a summer of almost complete crop failures, the weather during the autumn and early winter remained mild and pleasant up to the morning of December 31, 1885,” Laskowski writes, “which inclined people to believe there were in for an open mild winter.”

The crop failures of 1885 were not only a financial worry, but a practical one, because there wasn’t the cattle feed and other stores necessary for a hard winter.

“Late that morning the wind shifted to the north and a fine rain began,” Laskowski continues. “As the day advanced, the wind increased in force and the rain changed to snow as the thermometer made a dive below zero. Day after day the storm continued.”

The Topeka Daily Capital of Jan. 8, 1886, called the blizzard a “vehemence unprecedented.” While the entire country was punished by the storm, western Kansas got hit particularly hard; businesses, railroads and telegraphic communication all came to a stand-still as the snow came, the winds howled and the mercury dropped below zero.

“Two great blizzards hit western Kansas the first week of January 1886,” according to the National Weather Service webpage on the storm. “The first blizzard began on the first around noon at Dodge City and continued until the early morning hours of the third. During this time, seven and a half inches of snow fell … and wind speeds averaged 20 to 30 mph from the north to northwest. The lowest temperature was 12 degrees F on the third.”

The weather service is confident of the temperature because Dodge City had its own weather station, manned by the U.S. Army Signal Corps, which was first located on the top floor of the Dodge House hotel.

A second, more severe blizzard struck Jan. 6 and was accompanied by an artic blast that sent the mercury to 16 degrees below zero two days later, according to the weather service.

Residents were unprepared for the blizzards because the weather had been unseasonably warm — and because the storms struck so quickly. It was, until the Dust Bowl, the greatest natural disaster in Kansas history. Up to 100 people were killed, some frozen to death in the dugout cabins where they slept.

“There are several heartbreaking stories on how some of the people died,” the weather service reports. “Two young ladies froze to death near Minneola in Clark County. They were out walking, trying to reach their brothers’ house for shelter.” Their own home was filling up with snow. The women never made it and were found huddled together, dead.

Rabbits and birds were found dead on the prairie.

Train travel all but stopped because of the deep snow drifts. Most of the cattle in rail cars froze to death. Cows also froze to death in the fields — by the thousands. Estimates vary, but from 75% to 90% of the cattle in western Kansas died during the storms. As the animals perished, so did vast cattle fortunes.

In 1922, D.L. Simmons of Newkirk, Oklahoma, wrote a letter to the Dodge City Journal recounting his experience living on a claim nine miles outside the city.

“When daylight came, the air was white,” Simmons recalled. “It was like looking against a sheet. There was not a minute of the day you could have distinguished a cow from an elephant one rod from your door. … Almost everything, man or beast, that had been out during the blizzard died.”

He closed his letter by saying that nothing he had read about the blizzard, or anything that he had heard others say about it, was as bad as what he had experienced.

The blizzards of January 1886 in Kansas was just a preview of the hard times to come. The next winter, blizzards struck across the plains, and hundreds of thousands of cattle perished in what was soon called the “Great Die-Up.” The event was so catastrophic that it likely hastened the end of an era, according to American Cowboy magazine, by causing many cowboys to turn to farming.

“There have been other blizzards since January 1886 that have been just as bad,” according to the National Weather Service webpage quoted earlier. “As a result of this great blizzard and the consequences that resulted, changes were made in preparation for the winter months to help prevent livestock losses.”

These changes included fences to keep cattle from drifting onto the open prairie, stocking more provisions before the cold months, better and more accessible weather forecasting, and rotary snowplows that helped the railroads clear drifts.

While the blizzard that paralyzed western Kansas is 139 years in the past, last week’s winter storm made it seem less distant. We sometimes forget the impact of weather in our lives until something comes around to remind us — a twister, a flood, a blizzard.

Nothing upends your view of everyday reality like severe weather.

If you’re one of the lucky ones, you can survive the winter country with only a little inconvenience. Perhaps it’s just having to dig your car out of a snow drift or coping with plumbing in an old house. You might even have the luxury of reflecting on how the ice in the trees shine like gems in the winter sun.

But spare a thought for others not quite as fortunate.

There are people in your community who don’t have enough to eat, who can’t pay their utility bills, who don’t have homes to live in. The unhoused can freeze to death on a city street just as surely as people did a century ago in prairie dugouts.

If you can spare it, buy a little extra food the next time you go to the store and put it in a blessing box. Send a few bucks to a charity that you’ve checked out to make sure it is legit. Hand some dollars directly to someone in need, even though many localities discourage it. Make sure your pets are fed, watered and warm. Spread some seed for the birds. Help where you can, when you can, and in your own way.

The only weather we can change is in our own hearts.

Max McCoy is an award-winning author and journalist. Through its opinion section, the Kansas Reflector works to amplify the voices of people who are affected by public policies or excluded from public debate. Find information, including how to submit your own commentary, here.

Excerpts or more from this article, originally published on Kansas Reflector appear in this post. Republished, with permission, under a Creative Commons License.

See our third-party content disclaimer.